Salute To Wally Parks: From His Pen, Defending NHRA, Its Rules

Tenth in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

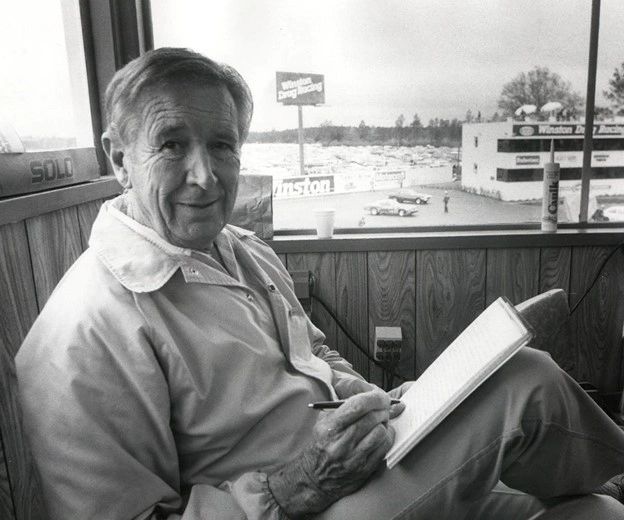

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the third installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

After a little creative writing in this first offering, Wally Parks’ essays below demonstrate not just his romance with hot rods but a fierce instinct to protect the sport and organization he so loved. . . .

HOLES IN HIS PANTS (unknown), by Parks.

“Crawling around on his knees, wearing holes in his pants and making funny growly noises, he pushed his truck through endless miles of dirt trails. He was a truck driver hurtling down the highway with an important cargo for its secret destination. His truck was a combination of two-by-four blocks, scraps from a nearby building site, hammered together with nails, bottle caps and other bits and pieces to make it authentic. It was a Mac. He wasn’t alone. Other kids his own age were bent on similar missions, propelling their own homemade vehicles around torturous curves in a roadway network that wove its way through the weed grown vacant lot. All were caught in the same reverie of make believe — a magical transplant to an imaginary world — which happily occupied endless hours in a small town’s eventless lifestyle. There was no cost involved — nobody had any money anyway and kids wore out their pants just scuffling, so this luxury could be forgiven. But each day’s action led to anticipation of an even greater day tomorrow, all based on a fantasy that was very real to its participants. It was a dream world centered on cars. And it planted a seed that would last forever.” It is hard for most people to understand that the man they admired so much could be so lyrical and poetical. The man drag racers loved or hated was a poet at heart. This is the full article.

——————————-

GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT (date unknown), by Parks

Although hot rods are generally thought of as being a recent development which has sprung up among speed-minded youth, such is not actually the case. With hot rods being essentially automobiles which have been subjected to the whims and reconstruct-tion ideas of their owners, they date back almost as far as the history of the auto itself.

Richard Parks: This was a variant of many articles on the history of the hot rod and was 12 pages in length.

——————————-

HORSEPOWER and the Glory (1970), by Parks

In the beginning, hot rodders created the NHRA. The time was shortly after World War II when returnees from military service, overseas and stateside, sought to reactivate their pre-war auto enthusiast hobby and knew that the best way to accomplish that goal was to organize.

——————————-

HOT ROD (unknown date), by Parks

They weren’t called hot rods when we left to join the military services in the early 1940s, but when we came back, after the end of World War II, they were. It wasn’t a complimentary name, generally speaking, and its use often was related to tire-squealing burnouts in otherwise quiet neighborhoods, in the dark of night. Anything sans fenders and sometimes the engine hood was eligible for hot rod definition, even more so if its exhaust was unnaturally loud.

Illegal street racing was becoming a fad in areas all across the country, usually identified as an unsafe public nuisance, which it often was. Cars and people who tinkered with them were not often at the top of the social ladder, and their on-the-street visibility made them a ready target for public scorn. Out on the west coast, in California, Oregon, and Washington, advantages in year-around climate made cars and hot rodding more popular than in most other parts of America.

An extra attraction, for a limited few, was the opportunity to run on the smooth dry lake beds of the Mojave Desert. For these privileged fortunates, racing fenderless across the flats with wheels and tires exposed was an exhilarating experience – once felt, never forgotten. In actuality it was the nearest thing to handling a full-fledged race car — sound, feel, wind in the face. Its appeal had a spinoff that extended to street-driving use. Besides, it was easier, after stripping the fenders and running boards for dry lakes racing, to simply leave them off. Around town, running without the hood was a natural for showcasing the engine and the visible extra add-ons that made it so special.

At the local drive-in stand, which was the standard gathering place, just to be looking at and talking “cars” was a satisfaction enjoyed by followers of this new “hobby,” to say nothing of the joy experienced by a car owner as onlookers ogled his pride and joy.

This was the full article.

——————————-

FUNNY CARS (late 1960’s), by Parks.

Drag racing’s “Funny Cars” have in a few short seasons become top challengers to the wild 220-plus MPH fuel dragsters for the sport’s star ratings. The emergence and growth of the funnies in popularity has been a normal part of drag racing’s unique evolution — this is an activity in which the expression of originality in design is a major driving force.

——————————-

HERE’S TO THE HEROES (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine)

Like any other rules-making organization, ever since the NHRA was formed, it has had its share of detractors. Some were simply resisting the idea of regimentation, in which someone else was calling the shots. Others were ones with sufficient backgrounds to challenge, resist, and condemn the rules-makers’ efforts to predict and try to avoid problems that might become hazardous if not given preventive attention.

Many of NHRA’s earliest rules of racing came from the organized speed trials held on dry lakebeds in the California desert. Other rules, like ones designed to protect against clutch and flywheel or transmission explosions, caused by extreme stresses of standing-start acceleration, came from cooperative evaluations by the manufacturers of products involved. In this respect, SEMA members were valued contributors. Early on, NHRA’s volunteer technical committee members were hot rodders themselves – most with car-building experience and some as active racers.

In all cases, the formulation of rules or guidelines was considered a serious and often restrictive, but necessary, obligation.

The NHRA “Safety Safari” [Richard Parks: the first two were Drag Safaris, the 1956 tour was a Safety Safari] tours of the 1950s revealed countless potentially dangerous elements in numerous contestants’ cars, and first-time drag races conducted in many locales were a wealth of information that influence many of the rules still in effect today.

But there were the objectors, as there always are — ones whose philosophies, good or bad, led them to oppose the ‘establishment.’ It happens in all walks of life, and in NHRA’s case, open criticisms of its regulatory decisions were often long, loud, and media-aimed. There were such offbeat laments as opposing a simple proposal that called for a small 3-inch visor on the cowl of hoodless front-engined dragsters, to deflect oil or fuel from the driver’s face – and also voiced criticism of other safeguard proposals, calling them NHRA’s “silly rules.” And when NHRA mandated transmission reversers, to eliminate time-consuming and sometimes dangerous push-starts, objectors were there with hysterical outcries, no matter how valid the reasons were for progressive changes in the functional rules of racing.

Some of the more venturesome, experienced racers came up with new ideas from time to time, slightly outside existing rules – but that is the name of the game in drag racing. Some worked, others failed, often requiring remedial changes and/or additions to the existing rules.

Through the years, NHRA’s technical department has relied upon input from many sources in maintaining the parity and safety of its regulations. Major changes usually are screened via consultations with car owners, crew members, drivers, and industry representatives.

Today’s “man in charge” of these operations has a background that includes Sportsman drag racing, successful roles as a Top Fuel dragster driver, track owner, and as director of two NHRA Divisions before being advanced to his present post. Also part of NHRA’s rules-evaluation team are a highly qualified former Top Fuel and Funny Car crew chief and a major car maker’s former racing rep, recruited by NHRA to supervise its complex but highly important industry related programs. All of that, plus the backing of an experienced, highly qualified staff of national and regional event-producers and technical experts, and the essential bases of responsibility are pretty well covered.

With all of these considerations, it seems pointless to ridicule a system that has protected the sport’s security and integrity for more than five decades, but some prominent careers have emerged in the past, based on a widely circulated practice of ridiculing the NHRA. But who, other than NHRA, is better qualified to ride herd on the rules in a field of racing that involves over 220 complex classes — from 330+ mph fuel burners to Junior dragsters – racing at more than 5000 sanctioned events each year? The answer is quite obvious. Nobody. Outstanding examples of never-ending changes in drag racing’s rules can be seen in the NHRA Motorsports Museum at Pomona, California, with its rows of showcase exhibits that reflect ongoing milestones in the sport’s progressive history.”