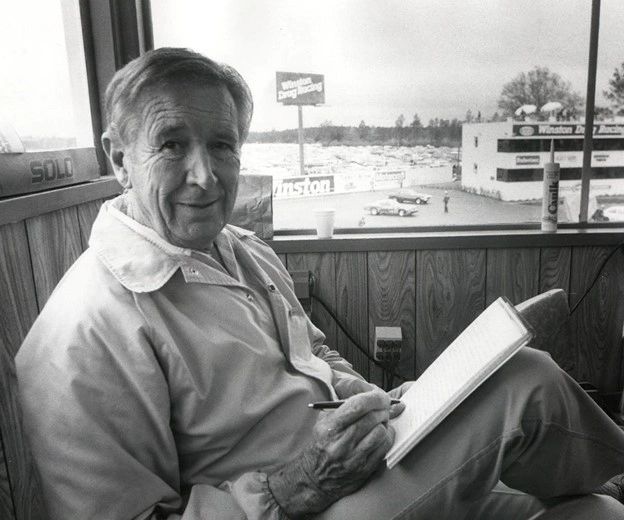

Salute To Wally Parks: From the pen of Wally Parks, Car Lover

Eighth in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the eighth installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

Here Richard Parks presents some articles his father wrote that tell of his early love of the automobile. . . .

FIRST REAL CAR (undated) by Parks.

“It belonged to Uncle Foss, my dad’s brother, who lived in Orange County, about a two hour’s drive from where we lived in a small community east of Los Angeles. I’d seen it during a Sunday’s visit, parked in the garage and unused, since Uncle Foss had another car and his two sons, my cousins, weren’t old enough to take an interest in cars. But I was. It was all black, a 1925 four-cylinder Chevrolet touring car, complete with fenders, top, the whole works and I was in love.”

This is the complete story. He probably meant to finish it later.

————————–

FAMILY (2000s), by Parks

I think I have always been hooked on cars, in one form or another. As a kid, when plastics were unknown and toys were unaffordable, my friends and I spent countless hours crawling through vacant lots, pushing little non-wheeled cars that we had fashioned from blocks of wood. We traveled endless miles on imaginary dirt roads, uttering full-blown sound effects that added reality to our bold maneuvers. The knees of our pants were always in shambles, but at day’s end the sheer joy of having ‘driven’ through all those twists and turns was pure euphoria, beyond description. I was born in the small town of Goltry, Oklahoma, in which my dad’s younger brother Winn proudly laid claim to having tossed stakes off the back of a buckboard wagon when the streets were being laid out. My parents were devoted and active members of the Methodist church, which was the town’s social center. Dad was a carpenter by trade and he had helped to build the little house in which I was born, which was adjacent to and somehow a part of the church property.

When I was two years old, hard times had set in all round us and our family moved to Bentonville, Arkansas, where we lived for a while with my mother’s parents, the Ravenscrofts. Then we moved again, into a rented house in Kingman, Kansas, where my grandfather, John Parks, had once built and operated the local flour mill. I can remember my grade school days in Kingman and having fished for perch on a trot line cast across the Pocomo River. And it was there that I got my very first bicycle, a gift from my dad, who had acquired it in what he called horse-trade, in exchange for some work service or article of similar value. My bike was full sized – and I wasn’t. It had no coaster-brake mechanism, which meant that you pedaled all the time. The only way I could mount it was from a box or alongside a high curb, of which there were not too many in Kingman at that time. But our house was on a slight hillside near the west edge of town and, once aboard, I could almost make the full circuit to downtown and back – almost, except for the long uphill return stretch, which meant lots of walking and much bike pushing.

My father’s two brothers, Foss and Winn, had moved from Kansas to California in search of job opportunities in the west’s building trades. It was their frequent letters of encouragement that finally convinced my parents that California’s prospects were generally better for raising our family than were existing conditions in Kansas. By this time, my sister Clyda was four years old and there was a new baby, Nelda Rose. With very little money for anything so venturesome, we sold at auction all our family’s household possessions to finance the journey west, keeping only what we could pack in, and on, our 1920’s Model-T Ford touring car for the planned westward tour.

There were six of us – dad’s mother, “Ma Parks,” my mother, younger sisters Clyda and Nelda, my dad, and me. Brother Kenny was born four years later. So we bravely set forth on our uncharted pilgrimage to Out West and its appealing but speculative promise of good things to come.

Lashed onto the car, with its traditional fabric top, was an odd assortment of essentials for the trip, as we planned to camp out each night along the way. In retrospect, it was a journey of journeys, not unlike that portrayed in John Steinbeck’s immortal “Grapes of Wrath.” The lack of westbound highways in those early days made it a choose-your-own-route experience. But, for me, it established an everlasting respect and endearment for that wondrous invention, the automobile!

Barely eight years old, I eagerly welcomed each new day’s adventures as we chugged along, from campsite to campsite, in our trusty Model-T. We traveled from Kansas down through Texas, once accidentally crossing a border into old Mexico, where only barbed-wire gates across narrow dirt roads defined one territory from another. Then we ventured into New Mexico on long, winding roads leading toward Arizona and its brand of Wild West, as we worked our way slowly toward California.

We shared nightly campsites with the sounds of passing freight trains, bawling cattle herds, coyotes, hoot-owls, other travelers, and imaginary Indians – all adding to unforgettable memories in the romance of a sparsely settled land. And through it all, there was for me an overlying sense of security provided by our venerable Model-T which, like a faithful horse, promised to take us to each mysterious new sundown’s destination.

One outstanding on-the-road experience stands out above all the rest, however — one that I feel is worth sharing. It happened after an extra-long journey across the Texas panhandle, where Amarillo was to be that evening’s intended stop. We had driven all day long, over what seemed endless miles of Big Sky country, but at nightfall Amarillo still was nowhere in sight. Finally, a town’s lights which we hoped would be Amarillo were visible far in the distance, so we kept on going. That windy night was bitter cold, and it seemed we might never reach our planned stop at a public campground on the western outskirts of town. When we did arrive, very late, we were on a barren flat plateau, with cold wind and dust whipping all around in gale proportions — not a great night for campers.

Among the few personal items my mother had brought along was one of her treasured possessions, a 9×12 Axminster rug, which we carried rolled up and tied along the driver’s side of the car. We had used it at times as a floor for the folding tent in which we all slept. On this particular night, arriving late and with wind howling outside, the carpet’s added comfort was especially welcomed. We also carried an upright Coleman kerosene stove, which was used to heat dishwater and warm the baby’s bath. After all the struggles of raising and securing the tent, enduring the all-night wind’s buffeting and arising before sun-up to get under way, we were eager to put Amarillo’s unforgettable campsite far behind us. After a hasty breakfast and before breaking camp, our dishpan of extremely hot water was set on the tent’s floor to cool a bit, for its use as the baby’s bath water – following which, my four-year-old sister fell backward into it and severely scalded her bottom. After attending her pain, re-loading belongings, and finishing our other chores, we all climbed into the Ford and headed due west – it had not been one of our long journey’s better nights!

On the road again – following what later would become famous as the nation’s well-traveled old Route 66 – we were chugging right along, headed for our next destination, when mother let out a cry of alarm! Pulling to the side of the road, dad asked what was wrong? ‘My Axminster rug,’ was mother’s response — and we all knew it had been left behind in our hasty departure from Amarillo’s campground. A look at the map showed that we’d traveled about sixty miles, and a return trip would add at least another hundred. A survey of our fuel supply, including the gas tank contents and a spare container strapped on the running-board, combined with a count of remaining funds, quickly suggested that we couldn’t afford the risk of an extra hundred miles. So with a painful but mutual parental decision, my mother’s prized Axminster was gone with the wind, so to speak, forfeited, perhaps, to some appreciative other camper.

We then worked our way westward and on to Albuquerque, New Mexico, whose lights on our late-night approach seemed as far away as the Pacific Ocean. Next day, we climbed over the mountains into Arizona, where we stopped overnight in a campground outside of Globe. It was at the foot of a mountain where an ore smelter’s 8 p.m. “fire fall” was a highly reputed shouldn’t-miss performance. Dad had looked forward to making this one of our trip’s objectives, and the sight of that fiery molten slag, falling hundreds of feet into the valley, was a magic spectacle for all to remember. From there, we traveled through Indian lands of Arizona, to Tucson and Yuma, across streams, over wood-plank desert roads and even riding aboard a current-driven, rope trolley wooden ferry, until we crossed the border into California. Bone tired, almost broke, but overall victorious, our epic marathon of Model-T endurance was completed – but were we home?

——————————-

GOOD OL’ DAYS? (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine)

Time was, when we had to travel endless miles into the desert to reach the scene of our long, overland journey’s anticipated dry lake time trials. For those who lived in the south, like Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, or San Diego, it was a several hours’ junket — up through the mountains via Mint Canyon road, past Palmdale and on north through Lancaster to an unmarked point where you turned abruptly east — off the highway and into the desert scrub. There were no directional signs — and in fact, no roads. Just a tangle of double rut tracks leading through the sand and in between the desert’s tall clumps of sagebrush. If you were coming from Riverside, Redlands, or east San Diego areas your route was more likely to be through San Bernardino, up over Cajon Pass, and through Adelanto, then west across the desert and into the same entanglement of rutted crisscross sandy trails. But in those times, as is often said, getting there was half the fun. It was the sheer experience of finding one’s way through unmarked trails that often led to who knows where? That provided new challenges for eager pathfinders. And dust clouds on the horizon were a reassurance that something was out there — like a distant airfield’s beacon welcoming an uncharted nighttime approach.

Most adventurers who braved these journeys drove their own cars, many of which were stripped-down hot rods [and]some hopeful of running in the events’ time trials. Ones that were under-slung, with dropped axles, et c., had to proceed cautiously lest their oil pans or engine sumps might drag on middle berms straddled by rutted wheel tracks. Once in the groove, there was no turning back. Along the tangle of trails leading in and leading out, there were no directional signs. You simply followed others’ tracks and/or just hoped for the best.

Driving in after dark was spectacular — especially if there was moonlight. And the night air was as pure and invigorating as one could ever hope for. And then, as the sun arose over surrounding mountains, it revealed the desert in all its glory — fresh, colorful and awesome.

Approaching the dry lake bed — whether (it was) Muroc, Rosamond, Harper, or El Mirage, was the fulfillment of a long-awaited dream. Here and there among the hummocks and clumps of sage were vehicles — some with little bonfires, others with people sleeping on the ground by their cars, after their long journey, from wherever. And beyond that was the seemingly endless expanse of dry lake bed that had summoned them all, to this mysterious, out-of-the-way Mecca.

Slowly and very gradually there was movement – toward what would soon become the center of the day’s attractions. Its hub would be the starting line, with a makeshift elevated perch for event control, timing and recording officials. No organized pits existed, as would-be contestants were scattered throughout the surrounding areas. Such things as fenders, windshields, and headlights were still being removed and stacked in heaps with each owner’s other belongings, before joining similar others as they headed expectantly toward a gradually assembling starting lineup. No one, it appeared, was in a rush. Entry forms were issued at the starters’ stand, with a minimal fee charged per vehicle. Out on the lakebed in the predawn hours, some eager individuals couldn’t wait to take a run across the seemingly endless expanse of lakebed. Most returned safely to their pit areas, but some less fortunate (ones) suffered severe crashes — running into hummocks and each other. It was an out-of-control situation for the handful of officials running the events, who were fortunate there weren’t even mor mishaps. Tall stakes were driven in the hard ground on one side of a straightway course, usually one or two miles long.

Timing was primitive – stop watches to home-made [ones], but reasonably accurate. Cars were run one at a time, rewarded by a metal time tag for an extra 50 cents. By the mid-1930s, attendant crowds had grown to several thousand at some events, and safety controls had become much more difficult for the organizers to contend with. But the allure of driving back home, for the racers especially, was still strong – after reassembling their cars and proudly flaunting that distinctive white dust that signified, to the world at large, their having been at “the lakes.” Near the end of the 1930s, dry lake problems from over-use, too numerous accidents, and neighbor complaints caused California’s Highway Patrol to threaten its closure. It was then, in 1937, that a small group of car clubs’ representatives banded together to form the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) and undertook responsibility for solving the problems — with the production of better organized and safer speed trials events. Today, these 68 years later, SCTA still conducts its seasons of time trials on El Mirage dry lake north of Los Angeles. And as a well-qualified organization for timing and certification of land speed records, it has conducted its popular annual Bonneville National Speed Trials on Utah’s famous salt flats every year since 1949.

That the best of the Good Ol’ Days are still kept alive is to their everlasting credit – and many of the outstanding cars, motorcycles, and memorabilia that have made that history are on public display in the Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum, at the Fairplex in Pomona, California.

——————————-

EARLY DRAGS (2000 revised), by Parks

Drag racing, as we know it, had its beginning in the late 1940s, at a time when illegal street racing had become an unsafe and unpopular nuisance. Legal standing-start “acceleration” races had been conducted on a narrow road alongside the Goleta airport in California, by a hot rodders group known as the Santa Barbara Acceleration Association. Rumor has it that in that same year 1/8 mile acceleration matches were being run on a concrete strip that was part of Beech Bend Park camping and amusement center in Bowling Green, Kentucky. At the old Navy blimp base near Santa Ana, California, the Southern California Timing Association and the American Motorcycle Association teamed up in producing a ¼-mile Hot Rods vs Bikes drag event. And a short time later, C.J. Hart and his partner, Frank Stillwell, opened the first known commercially operated drag strip, on a side runway at Santa Ana’s Orange County airport.

Similar activities were about to take place at Pomona, California, where the police department had acquired access to an unused airstrip in nearby Fontana, for the Pomona Valley Timing Association’s car drag races, an experimental venture that ultimately gained a permanent racetrack at the Los Angeles County Fairgrounds.

Farther south, at Paradise Mesa’s airstrip, members of the San Diego Timing Association were staging their own weekend events, from which many of the sport’s outstanding pioneer contenders emerged. Results and findings from these events, combined with closely related elements of the desert time trials, were used in compiling basic guidelines for drag racing’s classes and operating procedures.

The quarter-mile distance had been generally accepted as a practical start-to-finish stand for competition. At some of the earliest events where clutch and transmission breakage posed problems for standing-start races, slow-rolling starts were tried, to ease the strain on parts, with a flagman as the official starter. But as other problems and discrepancies developed, the rolling-start system was soon abandoned.

Although much of its attention was focused on the member clubs and car club events, NHRA was actively involved with the evolutionary development of a still-new drag racing sport that was being picked up in many new locations.

Richard parks wrote, “Drag racing began long before 1950. There are records showing drag racing in the 1930s. This is the full article. It may have been revised.”