Salute To Wally Parks: More From The Pen of Wally Parks

Seventh in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

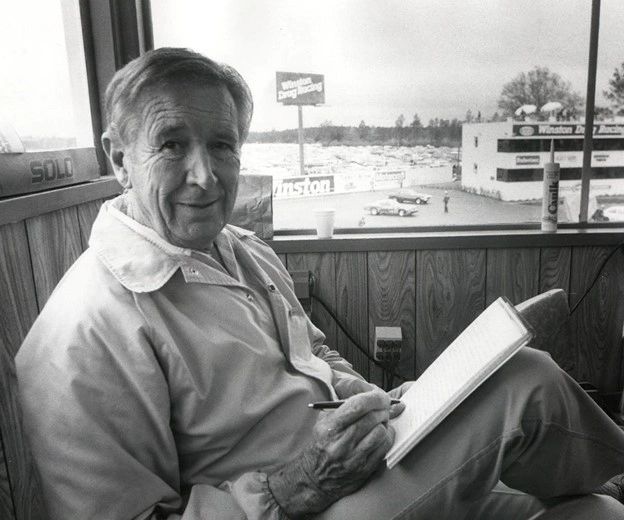

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the seventh installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

Here Richard Parks shares a second batch of articles and messages his father wrote through the years. . . .

CALIFORNIA HOT ROD REUNION – Living the Dream (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine)

It started as a dream, a fantasy idea cooked up by NHRA’s Steve Gibbs and Bernie Partridge, discussing the absence of a function that could recognize and honor some of the legions of past heroes who made their mark as outstanding achievers in the early years of drag racing.

They ranged from race car owners to pioneer track operators and industry associates, plus countless racers who gained their prominence with successful careers at the wheel of now-vintage drag racing cars. Nostalgia was the name of the game — an element that was growing more popular with each passing year as retired or abandoned cars were being re-discovered and returned to their original formats.

And what more appropriate place to honor these individuals and their early accomplishments, they agreed, than the veteran Bakersfield drag strip at Famoso, California which had hosted so much of drag racing’s early history?

Sure, they conceded, it was somewhat run-down and decrepit, but it fitted the occasion — and further it was operating under a master lease held by the National Hot Rod Association.

As the recall of drag racing heroes from the past divulged more and more qualifiers — mainly ones who had been active in western states drag racing and dry lakes speed trials — the idea blossomed into reality — one that hinted at the presentation of a California Hot Rod Reunion — at Bakersfield. That was in 1992, with Bakersfield the chosen venue and ‘nostalgia’ a natural objective for the recognition and celebration of past history. It was aptly named the California Hot Rod Reunion, produced by the NHRA Motorsports Museum at the Fairplex in Pomona, California.

Once under way the Reunion gained sponsorship support by the Southern California Auto Club, featuring a special ‘Reunion Spotlight’ by Justice Brothers Car Care Products, recognizing outstanding achievers in the world of race cars, street rods, and customs.

Initially, it was planned as a one-time presentation, with doubts expressed about its eligibility as an annual event. But that thought was short-lived, as the first year’s presentation proved a gigantic success.

Its format included an assembly of seldom-seen race cars, from early drag racing, dry lakes and Bonneville action, early street rods and an array of vendors with speed parts and souvenirs plus a swap meet loaded with hard-to find cars, parts, early publications and memorabilia. The event has grown in popularity ever since its introduction in 1992, so much so that a second version was introduced a few years ago, again at a vintage drag strip, at Beech Bend Park in Bowling Green, Kentucky. As the National Hot Rod Reunion, it, too, has become a gigantic success. This year’s California Hot Rod Reunion at Bakersfield’s Auto Club Raceway, Famoso takes place on October 6, 7, and 8, 2006. Early indications, in applications for entry and other participation, suggest it will be another barn-burner.

But that was its intent, as a salute to the past and an overdue celebration of those who played prominent roles in continued progress of a world in which we share personal pride — a once-renegade movement called Hot Rods.

——————————-

CALIFORNIA HOT ROD REUNION-15th Annual (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine)

Lookin’ Back – by Wally Parks. And speaking of lookin’ back, I have just come off an experience that was an all-time attention-getter, insofar as the history of hot rodders and the hot rod sport are concerned.

It was the 15thannual presentation of the California Hot Rod Reunion, conducted by the NHRA Motorsports Museum on the legendary grounds of the old Bakersfield Smokers club’s drag strip — now the Auto Club Raceway at Famoso, California. It was as if time had jumped back to the 1950s and earlier, as the array of street rods, customs, exotic motorcycles, and even rat rods was a challenge to historic gatherers anywhere. For sightseers it was a combination of yesterday’s and today’s finest examples of wheels and showmanship — a weekend’s experience almost without equal and topped with a massive outdoor mall that presented an endless lineup of premium car parts, countless rare and historic publications, and scarce other seldom found treasures.

In short, it was a hoot!

And adding more to its interests were lineups of vendors stands with rare memorabilia, gift souvenirs, apparel, and foodstuffs galore in a genuine car-carnival atmosphere. Topping it all, of course, was the on-track feature of Nostalgia and Vintage drag racing dating back to NHRA’s earliest years, with an inexhaustible lineup of veteran drivers, car builders and owners, crew members, and a veritable Who’s Who of hot rod industry pioneers.

It was, in fact, an existing replay of yesterday’s heroes — across the board — scores of whom were evident in Friday night’s reception at the Double Tree headquarters hotel, with between 300 and 500 celebrants on hand for the Reunion’s presentation of its annual Honorees awards, recognizing outstanding heroes of drag racing’s history. It was a rare night of nostalgic memories — with dignitaries far too many to be listed here.

But among the three-day weekend’s most outstanding and impressive “features” was the premium turnout of Nostalgia and Vintage drag race cars that were enrolled in three days and nights of on-track action. They came from all areas, including racers and race teams of widespread fame. And the quality and caliber of their restored and/or re-created vehicles was an absolute mind-blower. There were gas and fuel powered Dragsters, Funny Cars, Altereds, and famous Stockers — many with their former owners and drivers. In show-time condition, sheer beauty enhanced their performances.

Among the legions of outstanding celebrities still active at NHRA Reunions were such eternal legends as Don “Big Daddy” Garlits, Chris “The Greek” Karamesines, “TV Tommy” Ivo, Art Chrisman, Bob “Floyd Lippencott Jr.” Muravez, and countless other famous names, plus the genuine excitement of meeting such popular contenders as Herm Petersen, Butch Leal, Hayden Proffitt, Jim Nelson & Dode Martin, and countless other luminaries who were (and many still are) among the notable contributors to drag racing’s popularity and success.

Best of all — and especially for enthusiasts in the Midwest, East, South, and other regions far from the West Coast, the stage has been set for a similar presentation in 2007 — NHRA’s third National Hot Rod Reunion, now moving to the historic National Trail Raceway – on June 15-17 at Columbus, Ohio. And if the big success at Bakersfield was an indicator of what to expect, you can look for the very best in Nostalgic show-biz appeal and fast on-track action — at Columbus on Father Day weekend. It was a genuine Lookin’ Back experience that everyone who was there will long remember, and I’m glad I was fit enough to be among them.

——————————-

CAR CATS (date unknown), by Parks

JOIN our growing “fraternity” of people who know and care more about outstanding cars!

The NHRA Motorsports Museum is proud to introduce its all-new insiders’ group of car people — dedicated to the preservation and use of special road driven vehicles of all types — and sharing these interests with equally devoted friends. It’s called the CAR CATS — meeting monthly — May to October — at the NHRA Motorsports Museum. Annual dues — $50, which includes admission and vehicle participation in our first Wednesday monthly Cruise-Ins. Individual non-member entry is $10, plus special activities thru the year. All proceeds go to maintaining and upgrading the Motorsports Museum.

Richard Parks interjected, “The term CAR CATS was dropped in favor of a non-fee program called the Twi-light Cruise, with donations accepted from those attending. Also on the same note was another statement that seemed independent from the first request for a Car Cat membership. It read, “Our finish end TV coverage of winners after each final race has always been disorganized. Seldom do we ever see a recognized key sponsor representative, in the same old, same old rush to get the winning drivers words [presentation of trophies].It would seem to me that we could organize a setting and a system where the driver immediately goes and the sponsor rep could be available for pre-planned on camera coverage — in lieu of the hectic conditions that usually occur. I noted in the Las Vegas TV coverage that Vic Edelbrock was right there on camera with the Top Fuel winner, while no other sponsor rep was included. Edelbrock is an old friend, but not a dragster (word blurred), and I’m unaware of a sponsorship he may have had at the event?” This is the full note.

——————————-

CLASSES are a dilemma (late 1990s), by Parks

One of the major dilemmas NHRA faces today is with the number of classes that are included in its racing schedules — primarily at the National and Divisional points events.

While the number is healthy in growing fields of competitors, it is cumbersome in conducting some Divisions’ overloaded events and has curtailed NHRA’s ability to produce top quality, major-league shows at its National events — for fans as well as TV programming.

The combination of excess entries at most events and the amount of downtime consumed in rounds of running the professional classes have combined into a condition where each day’s show is extended beyond any reasonable time limits. Divisional teams in the Federal Mogul series are taxed beyond their limits in handling extensive fields of entries, while National event operations occupy far more hours of running than is reasonable for first class programs.

The nature of drag racing requires that a large amount of time be afforded the spectators for their proper appreciation of pits and manufacturers areas in addition to the main features on the track, but a more reasonable time schedule of fewer hours — especially on the final day — would be of advantage to one’s having long travel distances.

Today there are 222 classes included in our National and Divisional programs. Seven of them are Professional and 222 are Sportsman. All are important in the overall mandate of maintaining competition entry levels, and any endeavor to cut back on the numbers must be carefully considered.

The Pro picture is acceptable — except for the amount of between-rounds time and its effect on show coordination and TV coverage. But the Sportsman class volume is a problem that needs careful evaluation and appraisal of ways in which to reduce the number of eligible entrants for National events and still maintain the quality of their importance.

One way to approach this objective is by building the importance and significance of our Divisional racing events — the FedMo series — to make them more attractive, more visible, more promotable and more rewarding for the racers, sponsors, and the track operators. Building the prominence and success of these events could allow tighter limits of Sportsman entries at the National events to produce balanced fields for programmed competition.

To accomplish this objective, an all-new pattern needs to be planned — one that elevates Sportsman competition as its own series. A new system of tournaments within each Division can be introduced, with a prospect of having Divisional runoffs to determine qualifiers for a premium National Finals event. A points-scoring system within this new structure would select a pre-determined number of entrants, or finalists, eligible for entry in the major National events — possibly with regional quotas. Any system that can tighten the eligibility requirements of National events entry could be beneficial — for reducing the volume of such entries and ensuring the quality of those accepted — although “quality” is not a major concern in these times of outstanding vehicles and equipment.

In short, the entire competition system needs an overhaul. The Divisional events need a strong hype in promotional support to bolster event attendance. The National events’ racing agenda needs to be tightened for fewer hours and presentations and more professional “show-business” attraction. Four hundred-to-500-car fields are acceptable at most National events — anything larger may mean more in entry fees but becomes a handicap when the final day rolls around.

Building the prominence and importance of our Divisional (now WDRA/Federal Mogul) events is a long overdue priority, for countless reasons. The right kind of program could ultimately become the ‘Secondary Series’ we’ve been looking for — with potentials for unrealized growth. Our track operators have had little incentive to promote and advertise their points meets — with negligible help from us. A new focus and heavy concentration on developing a more exciting concept could benefit everyone involved.

This is the full article.

——————————-

CRYSTAL BALL (1996), by Parks

Let me share with you some thoughts I have had recently regarding the prospective future of NHRA and the drag racing sports-entertainment industry.

As we all know, the costs of racing are growing higher with each passing season, as they always will, and we have been experiencing a gradual decline in entries at certain events in some of our top-ranking professional categories and in a few of the more sophisticated classes of Sportsman racing.

While our present schedule of major national (Winston) events is having a successful year, it includes a few sub-standard facilities and/or markets plus some duplicated event venues, with some prospective new sites in the offing. After our disastrous first ownership production at Columbus, it seems logical that NHRA’s track improvement plans should include some down-the-road thinking, based on long-range projections.

We are committing high-investment dollars to this project to ensure its stature among the sport’s prime facilities. Located in one of America’s best market regions for motorsports activity, the Columbus site needs to be a premium theater for drag racing, designed to present the best possible showplace for the caliber of events that have made NHRA successful.

But we need to look beyond the routine of quarter-mile racing as the best that we can offer. And we need to consider a shorter distance — the eighth mile — as a potential new arena for racing that can be built into a prominent future. The eighth-mile is ideally suited for grandstand and suite spectator benefits, as it condenses on-track action to more easily followed start-to-finish racing plus a more visible range of the shutoff area. It also offers valuable benefits for television’s coverage, from staging to sand-trap area.

Performance in the eighth-mile has already passed the 255-mph range for Top Fuelers and can be equally exciting in other categories of racing. The number of runs per hour is multiplied by the shorter distance, while the closeness of race finishes is vastly improved. Far less parts breakage, due to less stress on components, ensures fewer time consuming oil-downs and is a critical factor in lowering contestants’ costs of racing.

Safety, too, is benefitted in the shorter competition course and its more adequate track shutoff area.

In planning new facilities, the eighth-mile allows more flexibility in design and use of available property, with cost savings in many construction details due to more compact layout arrangements and less acreage requirements.

To seriously consider any major adoption of eighth-mile racing requires a dedication to the promotion and development of this concept to ensure its proper introduction and potentials for popularity. As a mild departure from common tradition, it will take concentrated “selling” to cultivate its general appeal. Long-range evaluation should include the prospect that a well-organized schedule of events, at the right locations, could provide the “secondary series” we have long needed, for such locations as Phoenix, Memphis, Seattle, St. Louis, and perhaps even Chicago — and possibly the second events we have added at Dallas, Fort Worth, and Topeka, plus other prospective new locations. Were Columbus to be included as a ‘flagship’ operation for the series, with an Eighth-Mile Nationals as its premiere attraction, the likelihood of having a ready-made max turnout of contestants and spectators would be highly feasible.

Therefore, the revision of plans for National Trail’s enhancement tailored for the conditions of shorter course racing could make it one of the trendsetters in drag racing venues — aimed directly at continued future advancement.

Two major leagues in effect – one building an eighth-mile following and the other focused on the well-established quarter mile – could provide an annual calendar of activity accommodating 30 to 40 events – maybe 15 per series.

The eighth-mile program might serve to attract sidelined racers from NHRA divisions who no longer can afford or be competitive at the NHRA Winston major meets. In a program with options, the professional racers might be challengers for eighth-mile event points and awards either separate from or in addition to official points issued in quarter-mile events competition. The trend in new racetracks today is not one of building 2½ mile ovals. Shorter tracks afford much better viewing and less in construction funding. The same applies to football, where doubling the length of the field would provide no advantage to the game’s attraction. Compact performances in full view of ticket-holding viewers and television audiences are a proven and workable combination.

Properly detailed, introduced, and promoted as “tomorrow’s answer to drag racing’s development,” eighth-mile competition can become a true winner – but only with confidence and a conviction to making it work. Plus features far outweigh minuses in eighth-mile evaluation, and it’s worth our consideration.

This is the full article.

——————————-

DRAG RACING (unknown date), by Parks

Although drag racing is just an adolescent when compared to other auto sports, it has a performance tradition unmatched anywhere else in the realm of points, plugs, and power. From initial performance readings of 10 seconds, drag racing has progressed to its present level of sub-six-seconds times in a matter of only slightly more than 20 years. That progress is all the more remarkable when one considers that, prior to 1965, the sport’s championship schedule consisted of only two major events: the Winternationals at Pomona, California, and the U.S. Nationals, which moved to its present home at Indianapolis, Indiana, in 1961.”

There are many variations of this story.

——————————-

DRAG RACING (unknown date), by Parks

Drag racing was a thing you did on the street, usually late at night in some secluded area where the cops were less likely to appear and spoil the fun. Remote roads in and around the Los Angeles basin got more than their share of such use. Places like a stretch of Lincoln highway that led to the new Los Angeles Airport, South Avalon Boulevard; North Sepulveda and East Washington Boulevards all got their share of after-midnight or early-morning exercises. It was common practice to match several cars, paired side by side, in a makeshift race over a half-mile or so straightaway, each of the contestants waging his own race. Motorcycles, too, were often interspaced in the conglomerate lineup of vehicles assembled for individual matches with no other rewards.

It was a dangerous game, in anyone’s estimation, but because top speeds seldom reached over 60 or 70 miles an hour in the limited distances, few serious accidents are known to have happened, and it was all charged off to simply having a good time.

Most of the race challenges originated at drive-in stands, which were the popular gathering places for car enthusiasts of the ’30s and ’40s. They lent themselves admirably to a car-hobbyist’s penchant for showing-off his wheels and for just “talking cars,” a fad that was equally enjoyed by non-car-owner admirers.

In the late ’30s, a common expression in accepting a challenger’s invitation to race was, “Drag it out,” which could have been a forerunner to the “drag race” term’s later adoption.

After a remote race site was agreed upon, the contenders would quietly leave the drive-in’s parking lot en route to the selected rendezvous. But keeping such information secret was seldom accomplished and small crowds of viewers usually were lined up along the roadway to watch the action.

Participants in those early times had stripped-down Fords and Chevys, for the most part, in various degrees of modification. All were used regularly as daily transportation, and it wasn’t until later that abbreviated “specials” were occasionally brought into play.

While all this was taking place, countless complaints were registered by citizens and other motorists, demanding that the police put a stop to what was termed a dangerous public nuisance. Through it all, the Los Angeles Police Department, County Sheriff’s Department, State Highway Patrol, and law enforcement officials of the surrounding areas were besieged with demands for crackdowns on the perpetrators. It was in this atmosphere of unrest and concern that the members of several car clubs got together in an endeavor to protect their own interests. Some club members were active street race participants, while other clubs had posed strict taboos against the practice.

Media had taken strong opposition to anything unusual on wheels and reports of street racing incidents were blandished in headlines. The Los Angeles Chapter of the National Safety Council had proposed new legislation that would outlaw the on-street use of vehicles sans fenders or hoods, or with any degree of modification to increase overall performance.

In a preliminary meeting late in 1937, a handful of clubs met to discuss the prospect of forming a representative group to defend and improve their collective public image. At a second meeting, attended by the clubs, the Southern California Timing Association was formed, its objective to meet with law enforcement leaders and establish a co-operative program aimed at improved highway driving safety. One of the incentives was that of attaining permission to organize club speed trials events on dry lake beds in the nearby Mojave desert. Muroc dry lake was a location at which early automobile racers had frequently conducted such events; usually with minimal controls and often resulting in both in-transit and on-site accidents.

This is the full article.

——————————-

DRAG RACING NEVER HAD IT SO GOOD (1960s), by Parks

Drag racing never had it so good! After fifteen years of beating its way to respectability and popularity, the sport today is riding on a crest. But how long can it stay on top, or how soon will the ride turn into a wipeout?

——————————-

DRY LAKES: eager young car nuts (unknown), by Parks

Lying on the ground, rolled up in a blanket at the edge of the dry lake, with a canopy of stars overhead like nothing you might ever have imagined — that was euphoria!

But it was a fundamental part of going to the lakes, a California car-tinkerer’s paradise.

Waiting, in the pre-dawn hours, for that first ray of sun-up and the sound of engines being fired up was an anticipation that once experienced, would never be forgotten.

Here and there a campfire flickered, more as precaution to being run over by one of the night marauders who now and then drove recklessly in the dark. This was tradition in the 1920s and into the ’30s, when there was little organization or control over the large gatherings of contestants and onlookers who were attracted to the Lakes.

Muroc, it was called — the first and best location for speed contests — placed off limits by the Army in 1940, ultimately to become Edwards AFB and eventually NASA’s shuttle landing site. Its flat, white surface extended approximately 10 miles wide by 20 miles long, without obstructions or hazards, other than the conduct of those who drove across its surface.

This is the full article; but he often retold this story.