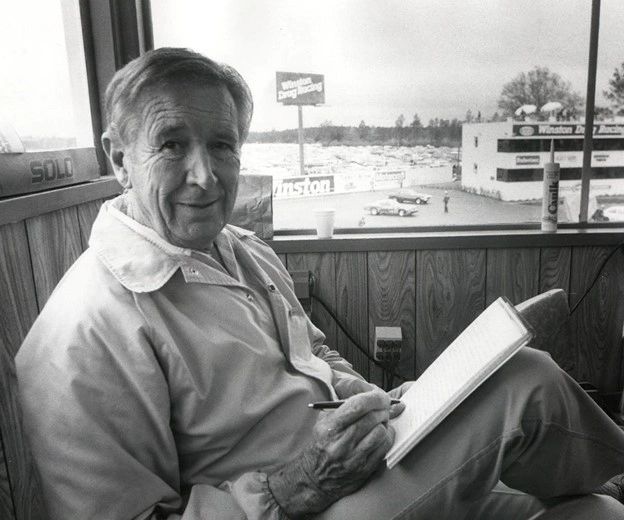

Salute To Wally Parks: From The Pen of Wally Parks

Fifth in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the fifth installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

Here Richard Parks shares a rich compilation of articles and notes from his father’s pen.

“Having gone through seven filing cabinets of dated events, I have now come to drawers of miscellaneous material that was loosely dated or with an unknown date. Much of the material copies from past stories what he said in his capacity as Hot Rod Magazine Editor or in speeches that he gave to groups around the world,” Richard Parks said. . . .

WHO I AM (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine)

“When we announced in last month’s issue of DRIVE that I would be contributing a Lookin’ Back column, we may have jumped the gun in neglecting to explain who ‘I’ am to unaware readers — other than as the founder of NHRA. So, here is a brief rundown of my background.

First, let me point out that most of my achievements over the past several decades have been a result of having been in the right place at the right time, and recognizing opportunities that could be used to advantage. No particular genius in that.

As indicated, I was hooked on cars from an early age. I made my first visit to the dry lakes in 1932 — my high-school-graduate year — riding with two friends in their ’25 Model-T coupe with a flathead Model-A engine. We went to Muroc dry lake, now Edwards Air Force Base, and needless to say, I was instantly captured. I ran my own car the following year — a 1925 Chevy 4 cabriolet — turning 82.19-mph. And I volunteered to help the event producers with any task they could find at which I might be useful. And they accepted my offer.

In 1938 I was one of a small group of club reps that formed the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) and thus became a member of the board of directors until World War II, when we put its operations in mothballs. In 1946, after four years of military service in the South Pacific, I was SCTA’s first elected post-WW-II president and the resumption of our desert speed trials was a primary objective.

In 1947, I left my test driver’s job at General Motors to become SCTA’s general manager. And in that year, we presented the first public display of hot rodders’ cars. We called it the Hot Rod Exposition, as an SCTA public relations venture to offset a growing bad image caused by illegal street racing in some areas. The show was highly successful, and it also was the spark that inspired Robert E. ‘Pete’ Petersen’s introduction of HOT ROD Magazine — featuring street rods and, of course, covering dry lakes activities.

In 1949, I implemented the campaign that gained permission for SCTA’s first Bonneville National Speed Trials, conducted on Utah’s famous salt flats. And in that same year, I left my SCTA position to become Hot Rod Magazine’s editor. In that capacity I was able to utilize its circulation to promote the cause of hot rods — both street-driven and in performance trials. It also allowed me to continue the joy of driving such pioneering vehicles as Bill Burke’s rear-engined bellytank and other rides of significance, at the lakes and out on the salt flats.

In March 1951, we announced the formation of NHRA (National Hot Rod Association) as a full-scale national membership organization. Its primary focus was on street rods and car clubs. Its motto, then as now, ‘Dedicated to Safety.’ Along with NHRA’s fast growth, we noted that among all the activities we offered to car clubs, there was no inclusion of speed or racing competition. Access to dry lakes was limited to desert areas, so we picked up on short-distance acceleration races that were fast becoming popular, particularly in western states — adopting many of SCTA’s dry lakes rules. And we cultivated a basic pattern that could be conducted in areas where a closed road or vacant runway might be available for properly controlled uses.

In 1954 I assembled the NHRA ‘Safety Safari’ — a team of hot rodders led by Bud Coons, a Pomona, California police officer — that toured the country in a campaign that introduced and demonstrated ‘organized drag racing’ to many communities from coast to coast. NHRA car clubs, as local hosts, were often able to present their areas’ first official civic-approved drag racing events. The Safari tours continued in 1955 and 1956, with the second year’s circuit ending at Great Bend, Kansas, where NHRA introduced drag racing’s first National Championships, the US Nationals — later moved to Kansas City, Oklahoma City, Detroit and finally Indiana, where it remains the sport’s largest and most prestigious annual event, at NHRA’s Indianapolis Raceway Park.

With Division Directors operating in seven geographical regions, NHRA was on a roll. Drag racing tracks were opening in areas across the U.S. and Canada, and NHRA chartered car clubs numbered in the hundreds. In 1963 I left a secure position as the editorial director of all five Petersen automotive magazines to devote full time to NHRA’s administration.

Now, four decades and two great presidents later (Dallas Gardner and Tom Compton), NHRA’s growth has been astounding. With 80,000 members and 140 affiliate tracks, it now stands as the world’s largest motorsports sanctioning body. As a still-active member of NHRA’s and the NHRA Motorsports Museum’s boards, I am looking forward to new ‘challenges and opportunities,’ while hoping to share some of hot rodding’s more memorable moments, in DRIVE magazine — Lookin’ Back.”

——————————-

WALLY TROPHY (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine).

“Why is NHRA’s ‘Wally’ trophy called the Wally when it doesn’t look at all like Wally”

One might ask the same question about Don “Big Daddy” Garlits, who in comparison with the legendary late “Big Daddy” Ed Roth bears little resemblance to the common concept of a Big Daddy. But it was a tribute to Don’s two little daughters, who traveled with him to all of the early events. When NHRA’s announcer Bernie Partridge first applied the “Big Daddy” moniker, that soon became Don’s popular trademark.

NHRA’s “Wally” trophy had its introduction in the 1960s, when as NHRA’s president, and inspired by the film industry’s “Oscar” trophy, I realized there was no prestigious similar award exclusively for winning drivers at NHRA’s major drag racing events – a vacancy that I felt needed to be corrected. On a yellow legal pad, I sketched my version of what a trophy of this importance might look like. That was simple enough — a driver in a racing suit, standing alongside a drag racing wheel and wide slick tire.

It was at the Winternationals at Pomona Raceway, and my first venture was to alert NHRA’s ace photographer, Leslie Lovett, that I might need him to shoot some photos for a special NHRA trophy that I hoped to create. A next move was to find a race driver who might pose for the occasion. And the answer was almost immediate, when standing by the starting line was one of our Top Gas dragster class drivers, Jack Jones, who obligingly agreed to pose for the prospective new and exclusive NHRA special award.

A next step was for me to borrow a dragster wheel and mounted racing slick, courtesy of M&H Tires owner Marvin Rifchin. And Lovett came through with front, back, sides, and three-quarter-angle photos that I sent to our trophy supplier Al Goldberg, along with the sketch of my “concept.” Al agreed that he was sure his model-maker could reproduce the figure for a casting mold — and I requested that, like the Oscar, it should not resemble anyone’s likeness (certainly not mine) and that it was to be an exclusive award, available only to the NHRA.

The new trophy’s issuance was a welcome award for drivers of winning classes at NHRA’s major events — but there were problems: some car owners wanted to keep the trophies for themselves. So, following a pattern set at NHRA’s Grandnationale in Canada at which the event sponsor, Molson, presented a special medallion to each of the winning drivers, I once again was a copycat in designing an NHRA ribbon-medallion featuring a likeness of the trophy — which remains an exclusive symbol of a driver’s achievement at major NHRA events.

So that’s how it happened and the reason for its name, the Wally. That it has become so highly prized and widely recognized is one of the most gratifying rewards I could ever have received in return for an “idea” that worked — that and an 8-foot tall golden replica, conceived by Steve Gibbs, that stands right in the center of the NHRA Motorsports Museum at Pomona. Ya gotta see it to appreciate it.”

This is the full article; there are two versions of this story.

——————————-

WALLY TROPHY (2006), by Parks (for DRIVE Magazine).

“Question — What is the background of NHRA’s ‘Wally’ award?

Answer — The ‘Wally’ award is an NHRA exclusive trophy, primarily for winners of major NHRA drag racing events and secondarily for presentation by NHRA to individuals and companies for outstanding contributions to drag racing and other elements of the hot rodding culture.

It was conceived and designed by NHRA’s founder and then-president Wally Parks, in 1960s. Its inspiration came from the Motion Picture Academy’s “Oscar” trophy, awarded annually for outstanding film acting and film productions — and awareness that drag racing was lacking in similar exclusive recognition for its outstanding winners.

To fill this need. Wally visualized a trophy that would pay special tribute to the winning driver’s achievements in each of NHRA’s racing category’s at its major National events. At that year’s Winternationals in Pomona, California, he drew a sketch of the trophy he had in mind. It was a typical driver in a drivers’ suit, standing with one hand on a drag racing slick tire, with helmet and gloves in his other arm.

He then alerted NHRA’s chief photographer Leslie Lovett to the possibility of his later need for some very special photographs during the event. A next move was to select a model to pose for a figure he visualized for the new trophy. It took no time to do, as he spotted one of the event’s drivers standing near the starting line, watching the race action. It was Jack Jones, a Top Gas Dragster driver, and he had all the paraphernalia needed for the shots. When asked if he would pose for what might be a new NHRA-exclusive award for race winners, Jones readily agreed.

Putting Lovett on alert, Wally then went to the pit area where he asked Marv Rifchin, the owner of M&H Tire Company, if he could borrow a mounted drag-racing tire and wheel, which Marv gladly provided.

Then, moving to a space near the bottom of Pomona’s timing tower, Parks directed photographer Lovett to shoot the front, back, both sides and quarter angles while Jones stood with the wheel and tire at his side. It all took but a few minutes, and the results of Lovett’s photography were just what was needed.

Next step was to contact Al Goldberg, NHRA’s trophy supplier in Chicago, to discuss the new trophy’s feasibility. Al agreed his model-maker could provide a likeness for the trophy, with NHRA paying for, and owning, the mold. And he requested that Wally’s sketch of the trophy concept should be sent along with Lovett’s photos for the model-maker’s use. And at Wally’s suggestion, it was to resemble no one — a spin-off from the faceless Oscar trophy. It was agreed from the beginning that the new trophy would be an NHRA exclusive — not for sale and available only through approved ordering via NHRA.

Originally, the trophy was to have been a driver’s award, but in reconsideration of the car owner’s role, it was agreed that a duplicate trophy could be ordered by the car’s owner at a discounted fee, so both parties could be properly rewarded. Still concerned about the need for an exclusive winning-driver’s award, Wally was impressed by the Molson awards at NHRA’s Grandnationale in Montreal — a large metal disc suspended by a colorful neck ribbon — and he designed a similar disc with a ribbon-mounted replica of the NHRA driver’s trophy, as an exclusive NHRA event champions’ award.

That drag racing’s most highly-prized trophy, now referred to as the ‘Wally’ is a tribute to its originator is realistic. But unlike the tall statue that stands in front of the Wally Parks NHRA Motorsports Museum at the Fairplex in Pomona, it does not pretend to be a likeness. The genuine jubilation demonstrated by racers winning their first “Wally” is a measure of its significance and unbridled appreciation — exactly what it was designed for. Winning more than one is a dream come true for those who can duplicate their winning achievements — an undeniable verification of their being among the best of drag racing’s best.”

This is the full article; there are other versions of this story.

——————————-

40th ANNIVERSARY OF THE U.S. NATIONALS (1994), by Parks

Welcome, race fans, to the 40th Anniversary of the NHRA U.S. Nationals. This event, since its origin in 1955, has been the biggest and most prestigious occasion on each season’s calendar of major drag racing productions. As the original “national” contest for drag racers who came from all across America to take part in its 1955 inaugural, the U.S. Nationals has continued to escalate in stature and prominence through migratory moves that included stopovers in Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and in Michigan before making its permanent home here in the hospitable State of Indiana. Indianapolis Raceway Park was a wishful dream in 1960 when a progressive group of motorsports-oriented businessmen proposed the conversion of a rural cornfield into a multi-use auto racing facility. Construction started that year.

In 1961, NHRA came to town, having accepted an invitation to conduct its number-one event on the straight portion of IRP asphalt that is the theater for each year’s U.S. Nationals.

Since 1979, NHRA has been both proud owner and operator of Indianapolis Raceway Park, with a year-around schedule that includes fast action on the banked paved oval and the road racing circuit, versatile on-site testing and hospitality services and a drag racing complex that is second to none.

This year’s homecoming’ is our salute to Indianapolis, the auto racing capitol of the world, home of the venerable 500-Mile Race for Indycars, the U.S. Nationals of drag racing and, new this year, the Brickyard 400 for NASCAR stock cars. We thank you for joining our party and its celebration of 40 great years of Championship Drag Racing, the US Nationals.

This is the full article.

——————-

40 YEARS AGO (1997), by Parks

The National Hot Rod Association, which has been formed in 1951 as a coordinator of car clubs and hot rod activities across the country, presented its 1957 National Championship drag races at Oklahoma City’s state fairgrounds, following two preliminary years’ productions in Kansas and Missouri. The popular NHRA Drag Safari team’s training tours, supported in 1954, ’55 and ’56 by the Mobil Oil Company, was discontinued due to widely publicized condemnation of drag racing waged by the International Association of Chiefs of Police — a stand that was later rescinded.

Oklahoma provided a warm welcome mat for the ’57 Nationals and on the following year’s repeat set a new attendance record for drag racing that lasted for several years. In 1959, the Nationals were moved to Detroit and a new location in the Motor City. It was there that drag racing had its first real introduction to America’s auto manufacturers, inspiring a relationship that helped influence the popularity of Stocks and Super Stocks in competition. That it stimulated the ‘race on Sunday, sell on Monday’ cliché among dealers goes without saying — and it also cultivated a vast parts-availability program in which racers could rely on local car dealerships as a source of quality products.

The 1950’s were teeth-cutting years for drag racing. generating fresh ideas and limitless theories aimed at the still-new sport’s long-range development.”

This is the full article.

——————-

50 YEARS AGO (1997), by Parks.

“The SCTA had been re-organized, following its World War II years of inactivity, and was again conducting events at Harper and El Mirage. At that time, I was a “guinea-pig” driver in the Burke & Francisco rear-engined, flathead V-8 powered bellytank lakester, and I had left a good job with General Motors to accept a speculative role as SCTA’s secretary and general manager — its first ever full time employee.

In that year, with Ak Miller as president, we developed what would be the first major auto show featuring hot rod cars. Called the Hot Rod Exposition, it opened on January 23, 1948, in the Los Angeles Armory. The event was produced as a public-relations endeavor for SCTA’s member clubs. It also was the initial launch pad for Hot Rod Magazine.

Supercharged engines had not been taken seriously in early dry lakes competition — not until 1946, when Don Blair’s roots-blown V-8 Modified turned 140.62 mph, literally blowing away all comers and prompting an immediate outcry for rule changes. While the first organized ‘drag race’ event has often been credited to the Santa Barbara Timing Association’s 1947 [Richard parks: I believe he meant 1949] airport at Goleta, California, a newly formed Mojave Timing Association’s event at Harper dry lake, in May, 1947, offered “drag races after time trials” as part of its agenda, on a standing-start, stop-watch timed ¼-mile paralleling its speed trials course. Goleta’s side-by-side races were soon to follow, as were other experiments, leading to an SCTA/AMA co-produced ¼-mile event for cars and motorcycles at the old Santa Ana blimp base and Orange County airport’s historic Santa Ana Drags. The fuse had been officially lit.

This is the full story.

——————-

60 YEARS AGO (1997), by Parks.

“A handful of west coast car club members (not yet called hot-rodders) gathered in Los Angeles to propose the formation of what would soon become the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA). The primary goal was to focus on driving safety, as a means for overcoming a ‘street racers’ image that was threatening their right to conduct organized time trials on the nearby desert’s Muroc dry lake. It all came together, with about 20 clubs in Los Angeles and surrounding areas, from San Diego to Santa Barbara, pooling their efforts to make the plan work. The dry lakes events were better organized, with approval and support by state, county and local law enforcement offices. Timed speeds ranged from under 100 mph to 118 mph, recorded after a mile’s run-up. The big majority of entries were roadsters, stripped of fenders and windshields for racing, many of them driven to and from the desert event site. It lasted until 1940, when the military annexed Muroc as part of the new Edwards AFB test facility, and then the racers moved their events to Rosamond, Harper, and El Mirage dry lakes.”

This is the full story.

——————-

496 WORDS ABOUT DRAGSTERS (unknown), by Parks

In the world of open-wheel competition, nothing can match the awesome performances that are routine in the sport of drag racing. And when Art Chrisman recorded a top speed of 140 mph in 9 seconds at the old Santa Ana drag strip in 1953, noted technical writer Roger Huntington declared it the ‘maximum attainable quarter-mile performance.’ You can make more horsepower, he offered, but you can’t put it to the ground! Meaning, of course, (that) suitable traction for a standing-start power launch (is vital). Those were days when a rear tire’s tread width was only seven inches, compared to today’s seventeen-plus and when a little alcohol, added to the gas tank, was an experimenter’s ‘hot fuel’ combination.

——————————-

CHARTER CLUBS, WHERE ARE YOU? (2002), by Parks

NHRA, in its beginning years, was a function that concentrated on the formation of car clubs. One primary objective was to provide incentives for members that might help to reduce growing problems of illegal street racing.

With its goal of seeking public acceptance for what had become known as a renegade movement, NHRA provided information on “How to Form a Hot Rod Club.” With examples of by-laws and constitutions, it also recommended that new clubs contact their local civic and law-enforcement officials, to enlist their support.

Safety was a major concern in those times, just as it is today. Realizing that their programs could not last unless they were safe, NHRA’s founders coined a slogan, ‘Dedicated to Safety’ that still remains a paramount guideline. A main conduit used to convey timely information was HOT ROD Magazine, which had fast become the bible for a new culture in cars and performance. Its monthly NHRA Bulletin Boards were of immeasurable value in covering, and crediting, new events and activities that emerged by and for the car clubs.

Racing was not necessarily a part of NHRA’s early agenda — even though its founding officers were hot rod builders and dry lakes racers. Instead it was road runs, safety checks, car shows and driving skill contests as the main functions practiced by car clubs and their members, often conducted as community service projects. But it soon was recognized that in areas other than the West with its desert dry lakes, there were few available facilities on which high-speed races could be run.

Some owners of street-driven hot rods had conducted experimental club events, but no consistent pattern of competition had yet been established. In a spokesman role, HOT ROD Magazine had suggested “A Drag Strip for Your Town” with a few basic ideas for accomplishment, using the quarter-mile as a racing acceleration distance. And even though rules and standard procedures had not yet been sorted out, a preliminary pattern was slowly being developed. Utilizing experience gained at California’s desert speed trials and a few pioneer drag strips, NHRA produced a set of guidelines borrowed from the Southern California Timing Association’s rules. Their adoption resulted in many of the sport’s earliest tracks being opened and operated by members of NHRA’s Charter Clubs.

When NHRA overcame the big obstacle of finding essential insurance, its drag racing sanctions program became a prime factor in the sport’s development. Car clubs all across the country adopted its pattern of a legitimate and achievable activity for members’ involvement. Just how many drag strips got their start as club projects is hard to guess. But the number was impressive and the non-racing activities by Charter Clubs also continued to grow. At one time it was estimated that more than 1000 car clubs worldwide were enrolled in the NHRA’s Charter program.

As a preliminary feature in the introduction of its National Hot Rod Reunion at Bowling Green, Kentucky, in June, 2003, the NHRA Motorsports Museum has begun a search to contact former NHRA Charter Car Clubs — especially ones that were active in early drag strip operations. A “Charter Clubs Corral” will be the gathering place to the special clubs and their members who were part of drag racing’s origin.

This is the full article.

——————————-

CARS FOR FUN TO KEEP YOU YOUNG (1960s), by Parks

The automobile since its earliest inception has been an exciting source of experimentation and inventiveness. Here in America, the country’s vast geographic nature combined with its economic structure has made possible a per capita auto ownership second to none. As a result, cars in America are generally gauged in number per family.”

——————————-

1925 CHEVROLET 4 TOURING CAR (unknown date), by Parks

In my first drive — in my first car — a 1925 Chevrolet 4 touring that I had purchased from my uncle in Santa Ana for five dollars — this is the exact view that I saw of a brand new 1933 Essex: parked roadside with the owner at the wheel and his wife at the door of friends, inviting them to see their brand new Essex — just before I ran into its left front fender!

My steering tie-rod chose that exact moment, at about 20 mph, to drop off into the street — allowing no time for me, in my unexpected situation, to apply brakes and stop the car.

I can still see the owner’s startled look. Result was a broken left headlight glass on the Chevy, and a large bump on my passenger friend’s forehead from contact with the windshield, after which he ran home to fetch my dad. That along with dad’s assurance that we would take care of damages to the Essex. Long story short — costs for repair or replacement of the ’33 Essex left front fender, hood side panel (thin metal all) and radiator were more than my car was worth, but its sale helped to underwrite dad’s overall expenses. Total driving time in my very first car — two blocks in about five minutes.

This is the full statement, but there are more versions of this story.

——————————-

1928 FORD’S MODEL-A (unknown date), by Parks

Looking out the widow during high school classes was one of my typical educational experiences. In algebra, I absorbed absolutely nothing in knowledge of the subject, but I learned a lot about steel construction as I watched the assemblage of our new auditorium at David Starr Jordan High School, on the main street of Watts.

Even more fascinating, however, was my well-remembered introduction to Henry Ford’s first Model-A. In another class, English I believe it was, back-grounded by a lot of horn honking, there going west on 103rd street, was a parade of cars led by a brand new 1928 Ford Model-A roadster!

——————————-

1929 MODEL-A CABRIOLET (unknown), by Parks

They were having a clean sweep sale, at the local Ford agency, and my car was sitting there on the used car lot, with a broom mounted on its back bumper. The selling price was $50 — a lot of money for me in those times of $12 per week wages — but I simply had to have it. It was a 1929 Model-A Cabriolet. The kind with a convertible top that didn’t convert, but it was just what I wanted. It ran well, and I had enough cash for a down payment, plus a job that warranted a monthly payment plan for the balance.

Few cars ever sounded as good as that Model-A when I tooled casually out of the lot and headed home. It had a light blue — faded somewhat — paint job that may have been original, but to me it looked like the finest car on the road. All through the business section I watched its reflection in store windows.

Everyone, I knew, was admiring me and my new car. But after a few weeks, its newness wore off and I needed something to add to its attractiveness. For one thing, I added a Road Runners car club plaque on the left-hand taillight bracket to match the license plate mounted on the right. That added some distinction.

The next big move consisted of removing the fenders, front and rear, leaving the running boards and splash aprons intact. This gave it a racy look, and then I just knew the world was appreciative of my outstanding car.

It served me well, however. I’d given up my laundry route and taken a new job. It consisted of making four trips a day into downtown Los Angeles from suburban Huntington Park, delivering office supplies and printed materials for a stationery store that specialized on quick service. I soon learned all the shortcuts and back alley entrances and took pride in the fact I was their fastest deliveryman.

The Model-A also earned its keep by providing lively transport in weekly hare and hound chases conducted by the Road Runners and other Southern California car clubs — usually in outlying orange grove areas and in rural sections of Los Angeles County and surrounding areas. But, alas, its performance was soon overshadowed and the urge came to move up into the ranks of the V8’s. The A-Bone became a good trade-in.”

This was the full article.

——————————-

ACCELER-ACTION – TODAY’s QUARTER-MILERS (1970s), by Parks

“Carefully, slowly, the flame-spitting 1500 horsepower dragster inched forward until its front tires barely edged into the light beam cutting across the drag strip’s starting line. The driver, clad in aluminized firesuit, gloves, facemask, helmet and goggles, tugged tensely at the brake handle, holding his straining four-wheeled projectile in place.”

——————————-

ADCRAFTER’S SPEECH (1958), by Parks

“It is my pleasure, and indeed a privilege, to speak to you in behalf of a segment of Americana that is too little known, and too often misunderstood. I’m referring to today’s HOT RODDER, whom I shall try to qualify to you as a desirable citizen who is an asset to your future.”

——————————-

ADVISING TOM COMPTON (unknown date), by Parks

Tom: The enclosed letter, which I recently received, may help to explain why I feel so deeply about NHRA and its future destiny. As you can see, it served a much better purpose than just marketing and sales — since it was a catalyst that gave access to a lot of people’s thoughts. The emphasis and the common bond were “cars,” and the whole culture rotated around that prime feature. It was our reason for being and the guiding inspiration that gave NHRA special significance to members, fans, industry and, in those times, the media. While the number of vehicles has increased tremendously in recent years, we have lost much of the magic that once was our expertise in describing and defining the components, parts and procedures that produce the one-of-a-kind vehicles that are the mark of what we do.

Early memberships were processed [by Barbara Parks] at home, after work, assigning member numbers, typing the membership cards and mailing other items such as decals, manuals, et c. which were included. Also, files were set up by state, town, and name under Wally’s direction; answered much of the correspondence both from members plus parents, civic, and law enforcement. She provided literature on organizing a car club, activity booklets, and lots of other literature to assist clubs in gaining support in their community. Later she provided drag racing literature which was included. Barbara worked on all phases of early NHRA, under Wally’s direction, setting up our division and working with the Division Directors and their wives. She supervised our new drag racing sanction programs, coordinated the paperwork for our three-year Drag Safari.

The first U.S. Nationals in 1955 at Great Bend, Kansas was memorable, as it brought members and clubs from most of the states together for the first time, making our staff feel that we really were a national organization! Our first real newspaper in 1961 was National Dragster. In 1961 we added a second national event, the Winternationals. During the Sixties, we added others and I primarily worked on producing the event program, coordinating editorial and advertising, plus printing and distribution. This lasted thru the Seventies. In 1960, NHRA moved to its first office on Vermont Avenue in Hollywood.

This is the full article.