Salute To Wally Parks: Backstory Of Hot Rod Magazine

Third in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

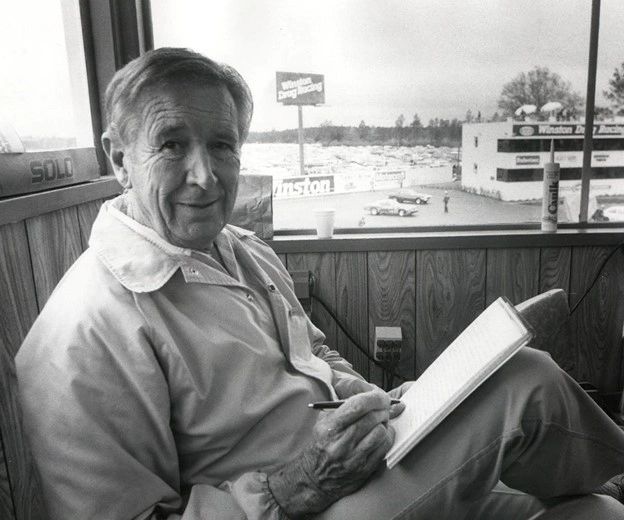

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the third installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

Here Richard Parks recounts the establishment of Hot Rod Magazine and his dad’s connections to the publication as well as to the enigmatic Robert E. Petersen and the Hot Rod Exposition 74 years ago, in January 1948. . . .

In the early part of 1947, Pete Petersen and [Wally] Parks began negotiations for the car show with a suggested date of late summer, but agreement between the various clubs in the SCTA held up scheduling until January of 1948. Hollywood Publicity Associates (HPA) was anxious for a date as soon as possible, as they needed the revenue, while the SCTA budgeted “hand-to-mouth,” or as funds were needed. By December all the terms had been met, the Armory in Los Angeles rented, sponsors and booths sold, and the exhibitors chosen and on schedule to participate.

What was needed was publicity and both HPA and Hot Rod Magazine (HRM) articles (with Parks submitting content as a freelancer) set about to publicize the car show. Dad wrote an article on the Hot Rod Exposition for HRM which appeared in the January issue (distributed in December or earlier). About 45 cars of all makes showed up for a photoshoot and the picture was published along with the article. Word of mouth advertising and sales of tickets by club members also spread the news. The SCTA’s General Show Committee met on January 2nd to finalize the details. Present were Parks (General Secretary), Ak Miller (SCTA President), Bozzy Willis, Mel Leighton, Thatcher Darwin, Fred Woodward, and Bob Hoeppner. Parks wrote some of the news releases which the HPA group distributed, one being on January 12th and this time stating that 50 cars would be on display.

Perhaps it is a point of trivia regarding when and where Hot Rod Magazine first got its start. One of the rumors that I believed for years centered on the animosity between Petersen and Bob Barsky over the ownership of HRM. Barsky felt that HRM belonged to HPA as it was formed by members of HPA (Petersen & Robert R. Lindsay). That was not the viewpoint of the two Bobs’ (again Petersen & Lindsay), since they had created something unique that would continue long after the Hot Rod Exposition was history. Perhaps Barsky did demand that Lindsay and Petersen turn over HRM to HPA and that they could not sell the magazine at the car show. But that was NOT why HRM was absent on January 23-25 inside the Armory. It was the SCTA that denied access to HRM, and it was rather a silly and petty reason: the SCTA did not want competition!

Thatcher Darwin, the recording secretary of the Association, wrote to Robert R. Lindsay on January 20th with the news that the SCTA Board did not want HRM to conflict with sales of the SCTA Program. Darwin wrote, “We acknowledge your letter of January 19, regarding the forthcoming Hot Rod Show, and have given a great deal of consideration to the question of whether or not the Hot Rod Magazine should be distributed at that event. This topic was the subject of a special meeting of the Association Executive Committee today, during which we assure you, every phase of the issue was thoroughly debated. We have concluded that the sale of the Hot Rod Magazine at the show would not parallel the best interests of the Southern California Timing Association at this time. The SCTA will have its own illustrated program on sale during the event, and naturally we should allow no other offering, so similar in content, to detract from its appeal.

“We believe you are well aware of the importance we attach to improving the public’s concept of amateur automobile racing, and the Hot Rod Exposition has been carefully organized to impress our identity upon its patrons. With due respect to your excellent publication, we feel that it would distract to some degree the attention which we are endeavoring to focus upon the SCTA’s activities. We are sure that the wisdom of our decision in this respect will be immediately apparent. We intended that our good will and fraternal feeling toward your enterprise be exemplified by the generous terms of our contract with you covering the publication and sale of the SCTA Official Program. Please be assured that our decision is based solely on an appraisal of the SCTA’s best interest at this time and should not be interpreted as an unfavorable reflection on Hot Rod Magazine in any degree or as reluctance on our part to cooperate with your organization in the future.”

Richard Parks said, “I doubt whether SCTA’s Programs would have sold well with or without HRM being present to compete. Barsky was not at fault here. It was the narrowness of the SCTA that forced Lindsay and Petersen to sell HRM copies outside the Armory building.

The Hot Rod Exposition was held at the Los Angeles Armory January 23-25, 1948.

Wally Parks wrote, “Marvin Lee was a car dealer, hot rodder and SCTA drumbeater. Lee O. Ryan was the senior member of a small group of laid-off film studio workers in 1947. They formed a co-op called Hollywood Publicity Associates (HPA) seeking clients for their services — first of which was Earl “Mad Man” Muntz, a Los Angeles pioneer entrepreneur in the television sales industry. Among the organizers of HPA were Lee Ryan, Phil Kent, Rolly Mack, Bob Barsky, and Bob Petersen, who was an unemployed studio lot messenger and the youngest to join the PR group.

“Petersen’s awareness of hot rods, from his high school days in Barstow, led him to take notice of an anti-hot rod campaign being waged by media in and around Los Angeles, and instinct led him to believe that the Southern California Timing Association (SCTA) might be a prospective client for HPA. A phone call to Wally Parks, then secretary and general manager of SCTA, resulted in a meeting, at which I advised him that SCTA had no money. I added that I had a proposal for a first-ever hot rod show, aimed at public relations benefits for SCTA to help overcome the bad image hot rods were gaining as a result of some illegal street racing in surrounding L.A. areas. (I said) that perhaps the SCTA and Hollywood Publicity Associates might join forces in the presentation of a Hot Rod Show as a partnership agreement.

“Petersen liked the idea and suggested taking it back to Lee Ryan for his appraisal of its merits. A result was approval by a few of HPA’s members while others, citing no desire to be ‘associated with hot rods’, resigned. Long sessions with HPA and SCTA board members resulted in a pact, and the search was on to locate a proper site for the show — which resulted in a selected setting in the old Los Angeles Armory, near Exposition Park in Los Angeles.

“Agreement on a proper name was a wrangle, until someone suggested ‘Hot Rod Exposition’ and the first presentation of a ‘hot rod’ show was under way. Arrangement was that SCTA clubs would provide its members’ vehicles and volunteers to man the show booths, while Hollywood Publicity Associates would take on the promotion and ‘show-biz’ aspects and advertising. Young Bob Petersen was assigned to selling booth space and program advertising, a feat that he carried out aboard a ratty old Harley-Davidson motorcycle, visiting speed shops and equipment manufacturers in and around the Los Angeles area. It was in this venture that ‘Pete,’ as he was known then, recognized the fact there was no publication covering dry lakes or other activities that were fast growing popular among hot rod enthusiasts all across the country.

“‘Why not?’ he thought, and his first move was to put together a dummy of a small magazine which he first labeled ‘Auto Craft.’ He shared the idea one night with me, whom he invited to join him in publishing a new hot car magazine. Time and circumstances of a heavy workload with SCTA made my acceptance impossible. I did offer that, ‘If you do it I’ll give you all the help that I can,’ recognizing the new advantages of promoting SCTA.

“Fortunately, Petersen had a friend, Bob Lindsay, whose father published a dog-lovers magazine, ‘Tailwagger’ and who offered to help them with counsel. Lindsay, who also was a film studio writer, liked the idea and agreed to join as a partner in the project, offering use of his portable typewriter and ultimately arranging a $400 loan as start-up money. Together they agreed on Hot Rod as the magazine’s title, with ambitions for its introduction at the Hot Rod Show. But such was not the case, as one member of Hollywood Publicity Associates took exception to the magazine, claiming HPA’s rights to part ownership, and the new co-publishers had to ‘introduce’ their magazine on the Armory sidewalk.

“From its first edition in January 1948, year of the show’s debut, Petersen and Lindsay shared responsibilities, with Pete as its advertising hustler and Lindsay as a writer and general office administrator — a good combo.

“The first edition of Hot Rod was a 5,000-copy run which they convinced a local printer to produce – on speculation of growth. With no other contacts, they likewise gained a small space in a newsstand off Hollywood Boulevard for its sales introduction, and they hawked the first editions in the stands at local racetracks. Petersen’s short military training background had taught him the fundamentals of photography, and with a borrowed Graflex he covered dry lake events and other hot rod activities, plus car features and performance parts offerings that were especially aimed at the new magazine’s readers.”

Wally Parks wrote in a topical fashion, even as an editor. He was stirred to action by a questioner or by the circumstances that arose. Often the situation was something in the news about wild hot rodders causing trouble and he would immediately step forward and write an editorial or harangue the offending official or reporter. There were no “wild” hot rodders, in his mind. They were innovative and creative people who loved the car culture. The troublemakers that were labeled hot rodders were not part of the legitimate car culture in his eyes. They were “squirrels” (lawbreakers), and he showed no mercy towards them.

Writing topically is a boon for historians who love to compare multiple sides of an issue, but it is redundant to the typical reader who simply wants to hear a story and isn’t concerned about how many versions of the story there are. I found it time-consuming to merge all his stories into one version; also by doing so, I changed his views even if I did not mean to do so. A good case in point is his relationship to Pete Petersen, who I briefly knew. Dad would have a different perspective on Petersen, based on the differing questions that people asked him about Pete.

Robert E. Petersen was also known as Petersen, “Pete,” Bob, Robert, “Boss,” and a few expletives, depending on how you felt about him. He was a quiet gentleman who controlled his passions, even though his passions were strong. He was also charismatic and likable as a friend and colleague, though he knew what he wanted to achieve and did not tolerate opposition to his goals. He had to preside over some extremely talented men who made his empire thrive, but although he took a hands-off policy himself. He hired business managers who were utterly ruthless. On one occasion, in order to keep the balance sheet from going into losses, his business manager went up and down the list, firing employees in a random manner (but did not touch his editorial staff). Some employees at Petersen Publishing Company (PPCO or PPC) disliked Petersen, and they absolutely detested his business manager. It was a place that was considered “Heaven” to work for and “Hell” to survive at. Yet Robert E. Petersen kept Hot Rod magazine and Trend, Incorporated healthy and prosperous, and that started the careers of men whom we revere in the media to this very day.

There are as many stories and opinions about Pete Petersen as there are about my father, and the truth is sometimes elusive. What is clear-cut is that both men flourished together until they reached a point where to continue to grow, they had to leave each other’s company.

One of my father’s complaints was that Pete tried to get control of the NHRA early – something that my father felt belonged to everyone just as long as he could oversee that it didn’t become a strictly commercial business. In my father’s thinking, the NHRA was not a business. It was a crusade. But just as telling is Petersen’s view that the NHRA originated in his offices, with staff he paid, loans to the NHRA that he gave, and with legal advice from Robert “Bob” Gottlieb, and his other private attorneys. Gottlieb was a hot-rodder and close friend to both Petersen and Parks and a major reason for the success of Trend, Incorporated and the NHRA. Petersen also funded and sponsored many activities that promoted the fledgling NHRA and straight-line racing in general. In Pete’s mind, why shouldn’t he “own”the NHRA or at least control it since it was so dependent on him in the beginning?

I’ve tried to track down all the stories on PPCO, as they are fascinating. Who could not love a corporate head whose policies called for hiring only talented and beautiful models to work as secretaries? If you held similar views and hobbies as Petersen, there were dozens of magazines that he created for profit but even more than profit since he loved the subject. Petersen was not wealthy as a young man. People who met him in his early life knew that he would soar high in the world. Movie starlets and actors were fondly loyal to him. In his earlier movie studio days, he was more than a Public Relations man, messenger, or errand boy. It irked him to be called a “go-fer,”as if he had no talent himself. Many racers told me stories, unconfirmed, how he would rush to get some actor out of a jam before the newspapers got hold of the story. I saw actresses such as Ruta Lee, Debbie Reynolds, and Larry Hagman at the Petersen Automotive Museum events, and the respect they had for Pete Petersen was real.

Everything that Petersen touched seemed to turn to gold; he was usually in the right place at the right time with the right idea. He made money in air travel, real estate, and publishing enterprises. Petersen and my father were alike in many ways. They were hard driven, married, each had two sons, and both were generally beloved and respected. In my opinion, the two men also suffered. Even the successful have tragedies. For Petersen, that tragedy was the loss of his two young sons in an airplane crash that was made worse since at the last minute the two boys took a separate flight that resulted in their deaths. Pete and his wife Margie were wealthy beyond imagining but had lost their two sons. I know he would have given all his wealth to get them back.

My father was never a wealthy man in material goods and didn’t realize until later in his life what a wonderful family he had and how much they loved him. My father had second chances to get to know his sons, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Pete was robbed of that blessing.

“Who knows if Robert E. Petersen hadn’t fulfilled his dream in forming Hot Rod Magazine, whether or not today’s world of street rods, dry lakes speed trials, drag racing, or the billion-dollar industries they’ve generated would have existed today? Hot Rod Magazine was established at a time of need, when any ‘modified’ vehicle was threatened by proposed legislature that would make it illegal for use on public streets, with media having a picnic beating up on all hot rodders. It also was when access to California’s desert dry lakebeds was in jeopardy, and the magazine became a lone crusader for safer cars and responsible drivers among its readers and enthusiasts.

“In those preliminary years, Petersen, whose military training had included photography, shot car features, and racing events for the magazine’s coverage, even hawking copy sales at local racing events. In 1951, Hot Rod Magazine was a key player in supporting that year’s formation of the National Hot Rod Association, when Petersen and his co-publisher partner Bob Lindsay advanced a loan for its incorporation, with access to the publication as a conduit for the organization’s promotion. So successful was Hot Rod Magazine that Motor Trend, a Detroit-oriented magazine, was introduced in 1949 under the banner of Trend, Inc. – a corporation formed in 1952 and later acquired by Petersen as the primary platform for Petersen Publishing Company.

“Hot Rod Magazine became the clarion for car enthusiasts whose ambitions included a do-your-own-thing objective in building and/or converting their vehicles, as street rods, custom cars, or for racing. In 1949, Hot Rod became actively involved in seeking access to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah for the Southern California Timing Association’s hot rod speed trials, the first of which were introduced that year. It was in the pages of Hot Rod Magazine, as far back as 1950, that the cultivation of drag racing as an alternative to street racing was first introduced. Working with law enforcement and pioneer drag strips in the area, NHRA and Hot Rod launched a campaign to provide and circulate guidelines and rules for drag racing, plus recommending them to local car clubs, law enforcement and civic leaders.

While this was taking place, there was an emergence of interest by manufacturers and marketers (speed shops) of performance equipment designed for street use and racing. It initial growth led to foundation of the Speed Equipment Manufacturers Association (SEMA), which ultimately became the Specialty Equipment Market Association. Its founders were pioneers in the development of accessories and parts primarily designed for racing and for use on the street.”

Johnny McDonald, a sportswriter and author from San Diego, wrote an article in which he stated that Petersen was living with his sister and father in Barstow, California, in the high desert, not far from El Mirage, and witnessed the hot-rodders as they made the trek to the dry lakes to race. He was in his late teens and working in a gas station on the weekends and his father was an auto mechanic. McDonald stated that it was remarkable that Petersen, at the age of 19 in 1947, should have found work with skilled publicity men in Hollywood. While the other members of the PR group found clients, it was Petersen’s inspiration that led him to Wally Parks. Dad suggested a hot rod show and Pete went to work on it. But it was Pete’s idea to create a small magazine that would promote the show. The success of the hot rod show and the magazine lured Wally Parks away from his position with the SCTA to take over editing the magazine that Petersen and his friend, Bob Lindsey had created.

“But I couldn’t afford to leave my job as general manager of the Southern California Timing Association,”Parks told McDonald. “So, he (Petersen) teamed up with Bob Lindsay, a wonderful writer with a public relations background.”

Parks finally agreed to become the editor in 1949 and said, “My job was to control the overlap of the magazines. Readership was there waiting for us . . . just had to find a means of introducing the magazine. Once we did, it really got on a roll! … (Petersen’s) assignment with the Hot Rod show was to visit speed shops and solicit ads for the program. He was a sharp, sharp young man. He hawked the magazine wherever there were races and was an excellent photographer, a training he got from an Army specialized training course.”

Petersen faced a great deal of skepticism and there were complaints that the title was racy and inappropriate. Yet Petersen wholeheartedly accepted Parks’ view of promoting the sport of hot-rodding and getting the message out to the general public that hot-rodders were not the bad guys that people called them. Everyone was surprised with the success of the Hot Rod show and the new magazine. Petersen would go on to create magazines that found a niche with skin divers, car, pilots, photographers, radio and CB fans, hunters, teenage girls, dirt bikers, and other titles. He promoted shows based on the formula that made the Hot Rod Exposition successful and supported the SEMA shows. Petersen had an eye for talent, picking people who had never been in the publishing field but who were enthusiastic about the activities that they loved. Petersen took a hand in supporting auto racing, which included road-course racing in addition to stock car, drag, and land-speed racing. He founded and endowed the Petersen Automotive Museum (PAM) that egged my father on to creating the NHRA Motorsports Museum.

The date of that First Annual SCTA Hot Rod Exposition car show was January 23, 1948, and it set the stage for every hot-rod car show to follow. The official title was ‘‘The Southern California Timing Association presents the First Annual Hot Rod Exposition and Automotive Equipment Display.’’ There would be a second Hot Rod Exposition in 1949, and then the SCTA would fall back into a lethargic sleep for half a century after my father left them.

The directors were Hollywood Associates, and the small and thin program sold for an unheard of price of 25 cents. It was the first time hot-rodders had tried this, and there was a lot of second-guessing and fear of a show failure. Car shows were not unknown prior to this, but they always centered [on] auto makers or elite car brands and wealthy socialites. This was a show for the masses, and no one knew if this idea would work, as the public saw roadsters and hot rods as lethal killing machines and hot rodders as juvenile delinquents.

I counted 47 cars entered into the show, low by today’s standards but quite adequate for 1948. And it was a first for hot rods. It was a MASSIVE success, not by our standards today but by the norms of the time. The gross on the show came to $38,748.66, almost double the total expenditures. Tickets accounted for $28,121.70, booth rental $10,256.41, and Program sales $370.55. Disbursements came to $20,699.76. The net profit was $18,048.90, a staggering amount for those times.

According to the contract, that amount was to be split in haf, so the SCTA could expect over nine thousand dollars, more than they ever had up to that time. It was a small venue site, compared to today’s car shows, many of which do not net near as much as the Exposition did in 1948.

As great as the profit was on this show, the real value lay in the experience itself. That show stirred other hot rod and custom car shows into existence; it breathed life into what we take for granted today. It changed attitudes, even though the public at large was unaware of the Exposition. The true value lay in how it changed the perspective of the media AND the hot rodders themselves. For the first time, hot-rodders saw themselves in the light of a successful segment of society and realized a level of respect heretofore denied them. The media saw the potential bonanza in mining a rich vein of news and stories in the hot-rodding community. The next year, the Grand National Roadster Show opened in Oakland to throngs of spectators and has been a crowd-pleaser for nearly seventy years. Other hot rod shows opened around the nation, and all of them owed their success to the foresight of the men and women of the SCTA.

The program featured the usual sponsors: Blair Auto Parts, Vic Edelbrock, Hollywood Trophies, So-Cal Speed Shop, Bell Auto Parts, Weiand Equipment, Elmer’s Muffler Shop, Eddie Meyer Engineering, Navarro Racing Equipment, Sta-Lube, Laird, and George Riley Carburetors. They also picked up Nesbitt’s, Bob Estes Lincoln-Mercury dealership, Ditzler, and Kogel Heads. But the big deal was the Ford sponsorship. Having Ford on board was a huge achievement. For the next two decades the Detroit car makers would help to turn my father’s dreams into reality. Name recognition also helped the show, and having Otto Crocker as the Chief Timer of the SCTA was an important addition. Crocker was well-known as a timer in boat racing, especially in the San Diego area. Boat racing was an entrenched sport among the wealthy, and you couldn’t have enough patrons on your side when you are trying to create a new culture.

The SCTA officials took up a whole page in the program. I believe they knew in their hearts they had a winner. If the show had failed it would have been an embarrassing setback to all of their hopes, aspirations, and future plans. Looking dignified and sharply dressed were Ak Miller, Wally Parks, Bozzy Willis, Mel Leighton, Thatcher Darwin and J. Otto Crocker. Dad had a forced smile on his face. Failure of the show would not injure the reputations of the other men, but it would seriously affect his future with the SCTA and his earning potential. He had a lot riding on this show.

The publicists changed their name to Hollywood Associates and dropped “Publicity” from their company name as some of their members objected to the whole concept of a hot-rod show. It was literally Pete Petersen who worked, sweated, coaxed, and prodded this show into existence, and yet he only used the title of secretary. Petersen never doubted for a second that this idea would fail. Pete Petersen was everywhere and though the SCTA actually put on the show. He was instrumental in its success. Robert M. “Bob” Barsky was listed as the President and managing director of the Exposition. I never met Barsky, but everyone I spoke to disliked him and felt his managing style was abrasive. I would like to know more about him to create a clearer picture of his history for the record.

Philip M. “Phil” Kent was the Vice-President and with Petersen, handled the sales and media. Petersen would later take Kent with him into Trend, Pete’s company that handled all his publications. Lee O. Ryan had the position of Treasurer and responsibility for the press and public relations; he also went with Petersen into Trend management. Ryan was the elder statesman among the group and a polished and erudite gentleman. My father was very fond of Ryan and looked up to him as an example of the successful manager. It is my opinion that the Hot Rod Exposition would never have occurred without the Hollywood Associates and especially Robert E. “Pete” Petersen and Lee Ryan. My father played an important role, and so did Miller and Leighton, but they could never have pulled it off without Petersen.

We must not overlook the exhibitors and vendors for without their support, both financially and through their combined prestige the show numbers would have dropped. When you have an enthusiastic vendor or exhibitor you have his whole company behind you and all of his employees and their families and friends. I found 58 exhibitors listed in the program, and some of them are still well-known: Barris’ Custom Shop, city and local government branches, National Guard, So-Cal Speed Shop, U.S. Army, Weiand and Weber, for examples. Other vendors were famous for years until they were bought out by conglomerates or the owners passed away and their businesses folded. Twenty Ford dealerships were represented and to reward Ford executives for their support, the show chose mostly Ford cars to display, although it was never advertised that way. There were 36 Fords on display with an additional 10 streamliners, all of which had Ford or Mercury engines. Against this massive display of Ford vehicles stood Meb Healey’s lonely Austin using a Chevy 6 motor. There were a smattering of non-Ford engines but for the most part it was a Ford show.

The owners of the dry lakes cars, partners, and those involved included some well-known names in the SCTA: Roy C. Aldrich (Mentone), Del Baxter, Tom Beatty (Glendale), Bill Benson (Ontario), Bill Burke, George Bottema (Norwalk), Bob Burns, Jack G. Calori (Houghton Park Village), Doug Caruthers, Charles L. Clark (Santa Ana), Charles S. (Chuck) Daigh (Paramount), Jack Detmers, Emil Dietrick (South Gate), Lute Eldridge, George Fabry, Lee Grey (Downey), Doug Hartelt, Meb Healey (Glendale), Stu Hilborn, Bob Hoeppner (Los Angeles), Stan Jones, John Kelly (Burbank), Keith Landrigan (Pasadena), Bert Letner, Howard Markham, Jack McAfee (Temple City), Art McCormick, Bob McGee (Huntington Park), Seymour C. Meadows (Yucaipa), Jack Morgan (Santa Ana), Jim Nairn, Henry Negley, Fred Oatman (Strokers Club), Harold Osborn (Azusa-Strokers Club), William R. Passer (Mentone), Phil Remington, Bob Robinson (Hollywood), Walter Rose, Paul Schiefer (San Diego), Regg Schlemmer (South Gate), Vic E. Schnackenberg (Orange), Harold “Scotty” Scott (Scotty’s Muffler in San Bernardino), Wade Seaton (Manhattan Beach), Randy Shinn, Doane Spencer (North Hollywood), Ed Stewart (San Diego), Jim Travers, Arthur Tremaine (La Habra), Bob Weinberg, and Fred A. Woodward (Whittier). The everywhere man, Bozzy Willis, along with J. Otto Crocker, made a miniature replica of the SCTA dry lakes meet in scale that was a popular feature.

Lou Baney and a crew of hard-working men built a complete roadster during the three-day show that drew a huge crowd interested in seeing how a car can be built from the ground up. Thirty-eight speed shops and equipment manufacturers donated parts in the construction of the roadster, and at the end of the show it was the main prize. I knew two of the crew members personally, Richard ‘Dick’ McClung and Johnny Ryan. Dick McClung was also a very good oval-track racer and in his lifetime he met and made friends with a number of famous drivers who included Pat Flaherty, Manny Ayulo, Jack McGrath, Don Freeland, Al and Bobby Unser, Johnny Rutherford, Troy Ruttman, and many more racers. He collected racing helmets and donated his collection to the Motorsports Museum in Pomona, California, where they are now on display.

In 1948, he survived a horrific crash at the dry lakes, flipping the car seventeen times. On the way to the morgue, the driver heard him moan and took him to the hospital. McClung turned to oval-track racing under the alias “Dick Webb,” which was a common practice in those days to avoid wives and employers finding out about one’s dangerous hobby.

Johnny Ryan worked for Nelson “Nellie” Taylor at the Taylor Engine Shop in Whittier, California. Ryan was a close friend of Taylor, and the two of them built some of the best flathead engines in the country. Both friends were members of the Gopher Car Club, and from Ryan I learned many of the stories and hijinks of that famous group.

Taylor was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge in 1944 and laid in the snow until help could arrive. It left him nearly crippled for the few years that he lived after the war. Ryan was on a passenger liner carrying troops to Europe in December of 1944. The ship hit a mine and sank just offshore in the English Channel, with the loss of thousands of American troops. Ryan was fortunate when a destroyer passed close enough to the sinking ship for him to jump over the rail and onto the deck of the ship below him; he was one of a handful of men to survive that disaster. Ak Miller was another survivor of the Battle of the Bulge, though severe frostbite cost him some of his toes.

I went to the Hot Rod Exposition the following year in 1949, and as a small child it was simply amazing to me, the crowds and excitement. I wouldn’t have another emotional feeling like that until Dad took my brother and me to Disneyland in 1956.

Thatcher Darwin wrote an interesting letter that adds more about the show, “… Robert ‘Pete’ Petersen, present co-owner and editor of Hot Rod magazine, and originator of the Hot Rod Show series…” At a later date Petersen would recreate the show in a series under the Trend label, but those later shows would never quite have the impact that the first two shows had in the public imagination.

To show the impact the Hot Rod Show had upon the clubs within the SCTA, it was revealed that the Gear Grinders sold 548 tickets and the Strokers another 537 tickets, with the clubs sharing in the revenue. This eased the financial burden on the members, and when my father asked for $625 to buy 500 rubber cones to mark the race course there was no opposition. The expansive mood of the association allowed for progress in the following. Portable toilets were leased, the secretary received a $25 raise, new clubs were asking permission to join, crash helmets were proposed in order to race at the SCTA meets, seat belts were mandated, and a huge fee of $10 per member was proposed for course work to repair damage to the lake bed. All of these proposals for support would have been difficult at best had the Hot Rod Exposition not succeeded.

It is taken for granted today that race-car drivers have helmets and seat belts, but prior to 1948 there was minimal safety gear. Every accident and injury caused the SCTA to rethink and refine its commitments to safety. When Dad formed the NHRA, he already had a good idea what to do along the lines of safety, and that had a tremendous effect on reducing injuries and deaths – which we take pride in to this very day.

I found a treasure trove of documents and signatures in the file. The first was a report by Parks, “SCTA to Hollywood Publicity Associates; 1st HOT ROD Show 1948. A survey of expenditures in money and labor on preparation of thirty cars, out of the 52 total, for the 1948 Hot Rod Show:

Total cash expended $2700.59

Labor @ $1.50 per hour $4243.50

Total $6944.09

Average per car $231.44

Fifty cars @ $231.44 per car $12,032.88

This includes only the actual preparation of cars for the Show and does not include time contributed during the Show nor expense of transporting cars or personal expenses during the Show.”

I don’t believe that this amount was reimbursed to the SCTA, as the Show did not raise that kind of money. This was probably compiled by my father for use as a press release to show the kind of money and labor that special hot rods needed.

He persuaded 30 individuals to fill out the forms which read, “Southern California Timing Association, Inc. Dear Sirs: To the best of my knowledge I have invested the following expenditures into preparation of my car for exhibition in the SCTA’s First Annual Hot Rod Show of January 23, 24, 25, 1948;

Cash expenses totaling $

Labor totaling $ Hours

This includes time and expenses incurred in transporting the car to and from the National Guard Armory in Los Angeles.”

The SCTA member then signed, dated and gave his address. The real value of these documents is the signatures. Photographs exist, but signatures are rare. I have heard about these men for decades but to actually see their names in writing brings them that much closer to reality.

John Alderson, chief engineer of the City of Los Angeles, wrote to Parks on February 6th, “Dear Mr Parks: I wish to thank you for the opportunity of a Fire Prevention Display at the Hot Rod Show at the Armory. Our Inspectors who handled our portion of it report excellent cooperation from the management and were enthusiastic concerning the reception of our display by the public which attended. It is certainly gratifying to have this type of cooperation from you. Thank you very much.” Lynn Rogers, Los Angeles Times Automobile Editor, in his column “Automotive Highlights” quoted Alexis de Sakhnoffsky that hot-rodders are indeed artistic and innovative creators. The success of this car show cannot be overestimated; plans were in the works to continue the show in 1949.