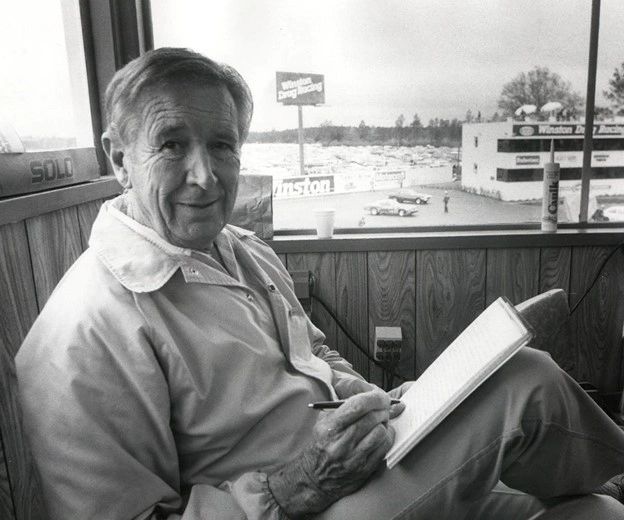

Salute To Wally Parks: More From The Pen of Wally Parks: Sweet 16

Sixth in a series, as told by Richard Parks

By Susan Wade

Richard Parks, the elder of National Hot Rod Association founder Wally Parks’ two sons, has given permission to Thoughts Racing share excerpts from his voluminous compilation of his family’s and father’s history. This is the sixth installment in a tribute to the remarkable man who passed away 15 years ago this September.

Here Richard Parks shares a rich recollection from his father’s story of his beloved “Bellytank Lakester.” . . .

BURKE/FRANCISCO & PARKS BELLY TANK(unknown date), by Parks

This bellytank lakester was also called the “Sweet Sixteen.” The story began:

This tall, gangly guy climbing out of the tank’s confined cockpit couldn’t wait to tell about how great the people are whose hobby is building and racing cars on the desert dry lakes.

“Take Don Francisco, for example,” he said. “His job is a fireman – on duty 24 hours and off 24 hours – but in between working shifts, he builds engines, and he’s one of the best there is. And [Bill] Burke here is a metal-craftsman whose imagination lets him build some of the most unusual combinations you’ll find in the world of speed and performance. He once was a player on the well-known Spoilers soccer team, but now this is his big thing. He doesn’t drive the cars – just builds them – but they are some of the most unique and original race cars you’ll find.”

The tall, lanky guy was me — a gung-ho fellow member of the Road Runners Club, designated guinea-pig driver of the bellytank.

And indeed this one was unique. Its body was fashioned from a jettison-type fuel tank as used with a military P-38 war plane – inside over the frame rails from a Model-T Ford, with the driver up front and the engine in the rear. This one — the first of its kind — was powered by a flathead Ford V8 that was assembled by Francisco, who also was a non-driver, content with the challenges of inducing maximum horsepower.

The driver’s cockpit contained an aluminum aircraft seat from a local salvage yard, as were many of the parts used by builders of vehicles built for dry lakes action. At the driver’s back was a large hand-built tank that held water for the engine’s cooling. Inside the cockpit was an aircraft steering wheel, a gas pedal, a hand pump for maintaining fuel pressure, an oil pressure gage and tachometer, a war-surplus seat belt, and a hand brake lever, mounted between the pilot’s knees that applied the two-wheel mechanical brakes, for stopping after a run through the course.

There was no rear suspension, the transmission being bolted directly to the rear axle’s differential case.

In concept and appearance, it was a first of its kind — a step forward between traditional dry lake modified and streamliners. Burke had built a front-engined tank-bodied car earlier — this one driven by Ed Korgan, who cracked it on his return record run but escaped injury.

When the day came for the Burke & Francisco bellytank to make its maiden run at El Mirage dry lake, the guinea-pig test pilot was Wally Parks, a member of the Road Runners Club of which Burke and Francisco were also members. Wally was well conditioned for the task at hand, having run cars of various types in the speed trials dating back to 1932, but none so radical as this one, as he put it.

With a push-start off the line, due to a high gear ratio, he eased into the throttle to avoid wheel-spin on the dry lakebed surface, then got the feel of it, and legged it.

Sailing down the course, headed for the finish line, I could hear the accelerated whining of the straight cut gears, as I glanced at the tachometer directly in front of me, with its bezel glass long departed. Then I watched the rpm hand go flying into the wind stream and automatically backed off for a moment. Using a predetermined signal, waving to the timing tower, I was able to abort the run and thus save the effort for another time. Even so, we ended with a clocked speed of 139-plus mph for the tank’s maiden trial — which wasn’t bad. Francisco was pleased with the run’s result and was certain there was much more left. So the team went about preparation for another attempt and hopefully better results.

When all was ready and we’d worked our way through the long line awaiting their turn at the timers, another push-start launched our second attempt. With added confidence, I pulled away from the push car, headed for the time traps with absolute confidence. Then, about one-quarter mile from the starting line, the steering wheel changed its position, but I was still going straight. I chalked it off to a faulty gear box, knowing it had come from a local scrap heap. Then it changed again, and I could still control it — so I legged it again and sailed through the timing traps. Using the usual technique of hauling back on the brake handle, I got stopped before the lake bed’s far end. And as soon as the push car arrived, we headed back to the starting area, with Burke at the wheel. Stopping at the timing tower we picked up our time slip – 148-plus mph! And no one had yet turned the elusive 150!

As we reached the lake bed pit area where all our stuff was stored, Burke climbed out of the tank almost speechless, his face the color of putty. Then he pointed down into the driver’s cockpit, where the right frame rail was severed and was lying on the tank floor. It had broken just back of the front axle, at a place where Burke had torched a notch for spring clearance – allowing the front axle to shift back and forth – and accounting for the steering’s position changes.

Based on the two prior runs and off performances, we knew the problem could be repaired and with another run, we could be the first to record 150 mph at the lakes. But there was a hitch — it was Saturday evening and Burke was committed to go home that night. And we all were riding together, and repair would require a trip into nearby Adelanto for access to a welder.

An argument ensued — the only one I ever saw with Burke and Francisco — and while that was taking place, Howard Wilson, driving Stuart Hilborn’s fuel-injected streamliner, sailed through the course at 150 mph — the first ever 150 mph clocking in dry lakes history. Others who shared experimental rides in the tank were Johnny Johnson and Bill Phy — neither of whom had been able to crack the 150-mph mark.

In 1949, at the first Bonneville Nationals on Utah’s salt flats, we had the tank ready to roll and were eager to see what it could do on this untried smooth surface. I was fortunate to have the first run and eager to show my stuff. In the past, at the lakes, there was always a fire in the engine compartment after each run, but it could be snuffed out easily with a small extinguisher carried in the driver’s cockpit. This time, before taking off, Don assured me there was not one but three extinguishers on board: one a small C02 bottle, another a tire inflator, and the other a hand pump Pyrene – all stowed beside the driver seat, within easy reach. What they didn’t tell me was that Burke had re-lined the two-wheel rear mechanical brakes, which had always been almost useless in stopping the car after each run at the dry lakes.

After the push-off start for our maiden run on the salt, I quickly found out that traction was a delicate problem that needed to be handled gently, but once under way, the experience was awesome. So I headed for the timing lights some four miles away — using the floating mountain in the distance as a convenient guideline. But just before entering the traps there was the distinct smell of a fire on board, so I backed off and grabbed the brake lever and trigger. Surprise of surprises; what they hadn’t thought to tell me was that Burke had re-lined the brakes and the tank and me were in a full speed spin — the first spin-out in SCTA’s Bonneville Nationals history!

As I frantically attempted to regain control we sailed off to the left of the course — and I immediately became concerned about how much scrubbing our front tires could take on the abrasive looking salt surface! And then I realized there was no way I could control the car’s direction at speed on this remarkably smooth expanse of salt — so I slid down into the cockpit and hung on, prepared for the worst. Down inside and looking up through the oval access opening, I could see sky and clouds swirling above me — along with the steady scrub scruff of tires on the salt. And I hung on until our speed had slowed and we came to a gradual stop. And then I heard the familiar light sputtering sound that told me there was a fire on board, and it was time to do something about it.

We had drifted left way off course in the ride’s swirly path and I could see no sign of life anywhere. But first things first — there was the fire to put out. It was always a small fire, the result of Burke’s oversize, oil-soaked intake manifold gaskets – but no serious threat. And besides, I had the assurance of not one but three fire extinguishers.

Unsnapping the hooks that held the tank’s top half in place over the engine, I activated the C02 — but nothing happened. Then I attacked the small flame with the tire-inflator gage cylinder, with the same non-results. So I resorted to the hand pump style Pyrene gun, which was futile, because it was empty. So the next available solution was an old shop rag, tucked under the seat front, and with that I casually beat out the flickering flame.

Then, looking in the direction of where I knew the course must be, I saw – not our chase crew but a small spot on the horizon, gradually growing bigger as it came closer. Then it emerged as a pickup truck as it came alongside, and in its seat an old friend, Julian Doty, who had just happened to see a dot on the landscape and drove over to investigate, he said. Shortly thereafter, Burke and the crew arrived, and we towed the tank back to the pits — sans any time or time slip but with the undisputable record of being the first to spin out in competition at the SCTA’s Bonneville Nationals. If nothing else, it convinced me of the salt’s absolute superiority as a safe venue for high-speed runs.

After my squirrely enclave [sic], we turned the tank’s driver seat over to Bill Phy, who had considerable difficulty in keeping it straight – until we found that the frame had somehow lost its alignment – a problem that couldn’t be fixed for any satisfactory runs at that event.

But the Burke tank, an original of its kind, had captured a record as the “World’s Fastest” in 1949, when it also was SCTA’s points champion, and it set a pattern still in use today among land speed contenders at both the dry lakes and Bonneville’s Salt Flats. For Bill Burke, Don Francisco, and others who were a part of its experimental team, it afforded countless hours of work, anticipation, and the joy of being part of a world that knows no bounds of satisfaction when an untested new idea works.

This is the first version of the story.

——————————-

BURKE/FRANCISCO & PARKS BELLY TANK (unknown date), by Parks

Ten years before my experiences in NASCAR’s 1957 Daytona Beach speed trials with “Suddenly,” a Plymouth two-door hardtop, as related in the March 16 issue of National Dragster, I was doing a similar thing — only this time at the wheel of what was the world’s first rear-engined bellytank, running in the Southern California Timing Association’s (SCTA) 1947 speed trials on a dry Mojave desert lakebed.

The revolutionary car was built by fellow car club member Bill Burke and powered by a Mercury flathead V8 prepared by Don Francisco. It used a P-38 fighter plane’s detachable fuel tank as its body – with the driver up front in an aircraft seat, barely back of the front axle.

It was Burke’s dream car, after having spotted some drop tanks in a military surplus dump, while serving with the Navy in the Pacific. Its main structure was built on a pair of Model-T Ford frame rails, with Model-A front suspension, and the rear-end was bolted directly to the clutch housing. The back half of the body lifted off for access to the engine, and its front section included an oval opening into the driver’s compartment.

Due to family uneasiness, Burke had promised not to drive the car, and Francisco had no desire to – so as a third member of the team, I became the tank’s eager and ready designated [Richard Parks: He also wrote ‘guinea pig’] test driver.

We had no inkling of how the revolutionary car might perform, but we knew it had a good engine and that the rest should be easy. The race course consisted of a one-mile approach to a quarter-mile time traps, plus almost another near mile’s shutoff and into the desert edge’s boondocks.

Snuggled down into the cockpit, I was ready for the challenging first-ride adventure –

with legs protruding out to the front axle and firmly belted into the driver’s seat, the minimal gages, and out-front vision unobscured. Mounted directly ahead was a tachometer – no matter that its bezel glass was gone – and within reach was a small fire extinguisher.

Pushed off from the starting line, I let out the clutch to direct-drive when we were rolling, and the engine fired instantly. And then we were off, the tank and me, headed for the time traps a mile away. It was pure wind-in-the-face ecstasy, and I listened to the whine of the straight-cut differential gears as we gradually picked up speed. And then a strange thing happened. The small aircraft-surplus steering wheel changed its position, about one-quarter of a turn – but we still were headed in the right direction, so I legged it. And then I watched the tachometer’s needle fly in the wind as we sailed into the time traps. A pre-arranged agreement with our timer allowed us to wave-off an unsatisfactory run’s time recording, in order to avoid one’s forfeiture of a limited number of timed runs. And that is what I did — rising halfway out of the cockpit for a wave-off, acknowledged by chief time Otto Crocker. But the aborted run still netted 139 MPH, and the realistic assurance that much more was there.

As a ritual, Burke climbed into the tank as we towed it back, past the finish line to pick up our time, and then jubilantly back to our pit area at the lakebed’s edge. A common target we shared, at that time, was the dream of being the first to reach an elusive 150 MPH at the dry lakes.

After some minor adjustments by Francisco, we put the car back in line for its second run. And this time, when the engine fired, I nailed it, as hard as the lakebed’s loose surface would accept, and, as before, the steering wheel changed its position slightly. But after backing off a couple of times, we seemed to maintain our direction, so I continued the run, past the timing stand and into the boondocks to await our team’s arrival.

We often had a minimum fire sputtering atop the engine after a run, resulting from a combination of cracked carburetor needle-seat and Burke’s oil-soaked homemade manifold gaskets. But this we could easily handle with our little CO-2 fire extinguisher. So with Burke in the tank, we towed back to the finish stand where we picked up our time slip — a cool 148-plus MPH! — enough to convince us that 150 MPH was within reach.

But on arrival back at our pit area at the dry lake’s edge, Burke climbed out of the tank; his face ashen. And speechless, he pointed down into the cockpit – where one of the front frame-rails was resting in the bottom of the tank. It had broken off at a place where he had torched out a chunk for cross-spring clearance – allowing the front axle to shift back and forth and causing the front end’s erratic steering.

For the rest of us, including me, we had just turned 148-plus MPH, only two less than that magical but evasive 150 mark! And as Don set about checking the engine and other components, it was agreed that the goal was within ready reach, if we could repair the broken frame in time for the next day’s running. All it needed was some welding work, even if it required running into nearby Adelanto, or Victorville.

But there was a hitch – Bill had also promised to be at home that night, and as our sole transportation was his car, towing the tank on his two-wheel flat trailer, we were stuck. Tempers flared and parts were loaded for the journey back home, as there seemed no ready solution.

Then a strange thing happened — Howard Wilson, driving Stuart Hilborn’s sleek streamlined modified (flathead powered, with Hilborn’s first fuel-injection system), sailed through the course at a cool 150 MPH and trashed our hopes of being first to reach this landmark objective. But one thing did happen however — a disgruntled crew did arrive home that night. And Bill Burke’s dream was the inspiration for many more of similar design, some still running at SCTA dry lakes and salt flats events.

This is the second version of the article. Howard Wilson went 150.50 on July 17, 1948.